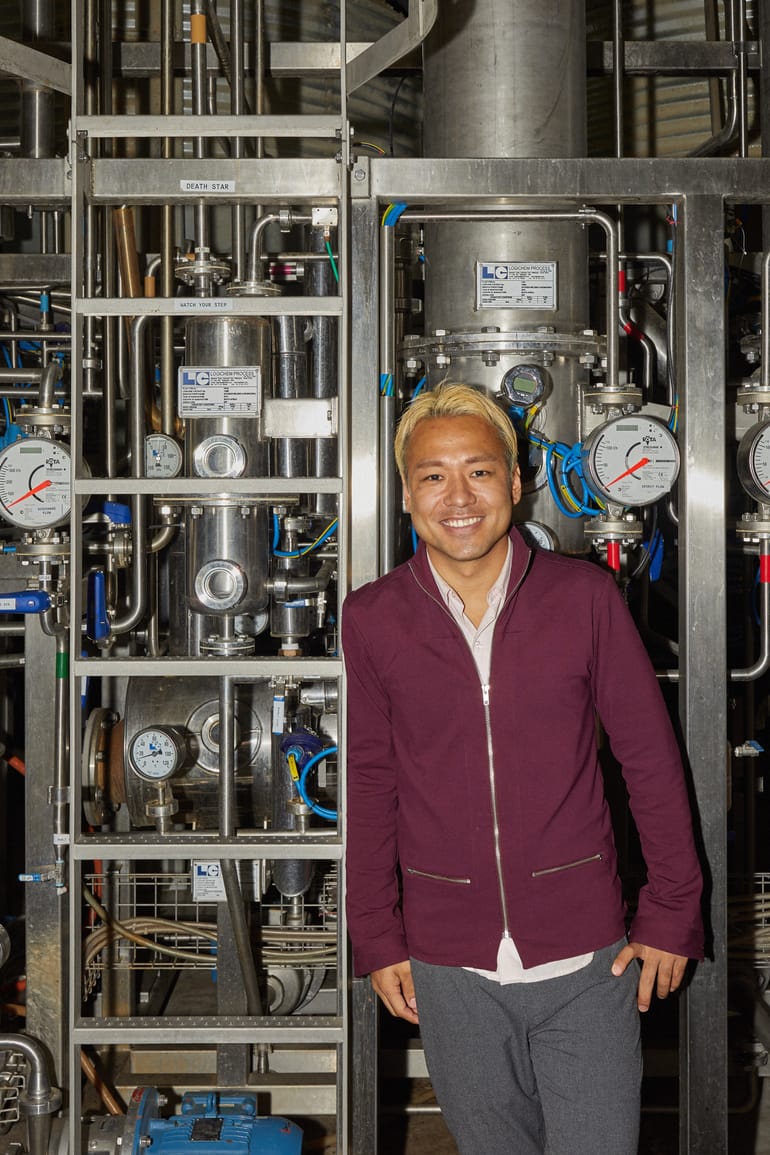

On Love, Trust and Running a Michelin-Star Restaurant

Born and raised in San Francisco, California, Brandon Jew's culinary journey is deeply rooted in his Chinese-American heritage. With a family lineage in the city that spans over a century, Brandon's connection to his ancestry has been a driving force behind his culinary ethos.

Brandon’s formative years saw him working in the rustic kitchens of Italy, as well as the vibrant food culture of Shanghai. Upon returning to the United States, he honed his skills under culinary icons like Judy Rodgers at Zuni Café and Michael Tusk at Quince. During this time, he met Annalee, who would eventually become his wife and business partner at Mister Jiu’s.

Mister Jiu's put Brandon and Annalee on the global gastronomy map. Marrying traditional Chinese flavors with California's abundant, fresh produce, the restaurant achieved a Michelin star within its first year, has been nominated for the prestigious James Beard Awards and has received nods from the Eater Awards and Zagat. Mister Jiu’s has been featured in publications such as Bon Appétit, The New York Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Eater, Saveur, VICE's "Munchies", and Food & Wine.

In 2020, Mister Jiu’s published a cookbook titled "Mister Jiu's in Chinatown: Recipes and Stories from the Birthplace of Chinese American Food" with Tienlon Ho. The book is an exploration of Chinatown's influence on Brandon’s culinary journey. Featuring recipes from the restaurant, the cookbook also delves deep into the stories and histories that have shaped the Chinese-American culinary landscape in San Francisco.

Brandon and Annalee live in San Francisco with their two-year-old son.

All right. Let's have a talk. Where do I want to start with you guys? I personally would like to know how you met. I love a love story.

[Brandon] At Bar Agricole, I served as the chef for a couple of years. Our mutual friend, Annie, once brought Annalee in for dinner. I saw her and was like, oh my gosh, I have to meet this girl.

Did you get introduced?

[Annalee] Well, this part of the story is interesting to me. When I moved from Florida to San Francisco, I only knew one person. He offered to show me around, so he took me to Mission Chinese. There, I noticed a tall blonde girl in a basketball jersey. I was drawn to her unique style. Fast forward a year or so, while working at Beretta, I saw her again. I recognized her from the jersey and asked, 'Were you at Mission Chinese wearing a basketball jersey?' She confirmed, and I felt this instant connection. I thought, 'We should be friends.' We exchanged numbers, though we were initially a bit flaky about meeting up. Eventually, we did hang out and became really close. That was Annie. And through this chain of connections, that's how I met B. It's fascinating how these random threads of connections can lead you to the most important people in your life.

[Brandon] After that day, I approached her to get to know her better. But I found out she had a boyfriend, so I understood she was off-limits. But after leaving Agricole, I'd see her around everywhere.

Like, randomly?

[Brandon] Yeah, like I’d see her passing by in a car. We’d say “Hey, what's up?” And then, so many other random times that we would see each other.

[Annalee] Yeah, we would.

[Brandon] And yeah, I just, like, kept trying to hang out with her more.

[Annalee] Yeah. And then I think one day I saw you outside, drinking a bottle of rosé by yourself at Tartine. (Laughs)

[Brandon] (Laughs) I had been working super crazy hard at Bar Agricole. Like I did this crazy stretch of, like, working seven days a week for a couple of months. I was a hermit, you know? And so when I got out of that job, I was just like, I'm just going to enjoy every fucking day. I’m going to drink a bottle of rosé by myself at Tartine.

[Annalee] So I said hey, do you want to go to my friend's sailboat? And he was like, Yeah, okay.

You're, like, literally taken from your rosé table to a boat by your future wife?

[Brandon] Yeah. I was like, “This is right.”

[Annalee] And then we partied for the next six months together. We had so much fun. You needed it. And B was doing meetings for Mister Jiu’s but it was slow moving, and then, all of a sudden, I realized that this was really serious.

[Brandon] Our relationship or the restaurant?

[Annalee] The restaurant, or maybe it all happened at the same time, you know? But I just remember all of a sudden it was like a clamp down of, like, we're doing this, you know? And things got really focused.

I mean, that's a big deal. You're dating, you're having a great time. Six months. And then suddenly you’re deciding to build this restaurant together. That feels as heavy as a proposal. Did it feel natural?

[Brandon] It kind of just happened.

[Annalee] There was no formal invitation.

[Brandon] Well, there was this formal—I mean, a time where I was like, okay, I need to know whether we’re going to be together or not. What’s the trajectory here.

[Annalee] Yeah. At the time, I was 28 and was progressing in my career. I found myself wondering if our relationship was just for fun or something more serious. I wondered if things were moving too quickly, especially since I had just come out of another relationship. Yet, I deeply admired you as a person. You embodied the qualities I'd always hoped for in a partner, from your tastes to your lifestyle. We also shared similar family backgrounds. Our shared experiences, like growing up going to church. These similarities were important to both of us. But being at that age, I was torn between commitment and the idea of exploring more. However, my friend pointed out the obvious—how in love I was with him, and how I literally hung out with him every day.

[Brandon] During that time, we saw each other every day for several months. It wasn't out of obligation; I genuinely wanted to be with her every single day. That period made me realize the depth of my feelings and the direction I wanted our relationship to go.

[Annalee] We spent every night together during that period. We were inseparable. I remember a time when I had to go on a trip, and I didn’t want to be away from him even for a day.

[Brandon] Yeah, it was like a high school vibe. That feeling.

[Annalee] We had such a good time. It's still such a great time. But you know, like first being in love. That was so special.

[Brandon] Just way less, you know, responsibility.

[Annalee] But yeah, you know how it feels.

Yeah. But that's the thing. That time is supposed to be just that time. So unique and special. You just have to treasure it when you have it. It's so beautiful.

[Annalee] Yeah. It just felt so good.

Well you know, the Gottman Institute suggests that the best way to predict a successful marriage in just a few minutes is to ask the couple how they met. If they’re glowing and positive as they tell the story, it’s likely to last. If the story is told with a negative perspective, that’s a sure sign that it’s doomed. You passed the test.

[Annalee] It is the best decision I ever made to commit to being together. And I think that when we did that, it was committing to do everything together.

[Brandon] At that point, we did almost everything together. We had this shared goal now of opening a restaurant. We brainstormed ideas, discussing the vibe we wanted to create and pinpointing the essential team members we needed. At the same time, we were deep into fundraising and catering.

[Annalee] From our tiny kitchen.

[Brandon] Our kitchen was so small, like the size of this table. I didn’t have a job anymore, so we were catering events for...

[Annalee] Some of the richest people you can imagine.

[Brandon] We're talking about the who’s who of Silicon Valley. The juxtaposition was hilarious, of how little we had. But during those times, I felt fearless. We had nothing to lose.

[Annalee] We had nothing, but in reality, we had everything because we had each other.

Dream combo, right? Like you guys can drive each other and support each other. But I also think having nothing to lose is this huge leverage that people underestimate.

[Brandon] For sure.

I remember feeling similar. When I had the idea for Haus, we were living out of a suitcase in other people’s houses, and money was so tight because I had stopped working to have a baby, and we’d spent everything on a home renovation that we literally couldn’t afford to finish. I had a three month old and no idea when we were going to have a home again. And I think that was why I had the guts to pursue it so hard. Like, why the fuck not. It can’t get scarier than this. I found that that was the source of my fearlessness.

[Brandon] I think now that I look back, I'm just like, wow. I was completely naive to the amount of responsibility I was in for. I was actually, you know, signing up for personal guarantees for things that I probably shouldn't have. My lawyers were freaking out.

Oh I remember having those talks with attorneys. Certain deals where they're like, “This is a very bad deal. You shouldn’t do this.” And I'm like, “but I have to.” Or at least that’s how I felt at the time. There were not other options available to me, and you sometimes have to take a less-than-perfect deal to move yourself forward.

[Brandon] I often reflect on the changes and challenges we've faced. Sometimes, being so in the day to day, it's hard to wrap my head around what we’ve built. Maybe you’ve been able to really see what you built with Haus now that you have some distance from it. But man, talking about these earlier times brings back memories of what we set out to do and the journey to get here. The vision we had, the community we wanted to nurture, we’ve been able to build that. I hesitate to use the word “success,” but…

The good news is you don’t have to articulate the magnitude of what you’ve done because so many other people can see it. We can see what you’ve built. You know what I mean?

[Brandon] It's still like a project to me. So it's hard because I'm still in it and I'm still constantly thinking about how I'm still trying to make it better.

Yeah.

[Annalee] And it changes all the time.

And it's both, right? It's both what you've already done, and it's the potential. And the space between you and your potential is always uncomfortable.

[Brandon] Yeah. And I don't know if that space goes away. You know, it's just… it's always just a little bit out of reach, but you put it there, because it keeps motivating you.

It's harmful and it's useful.

[Brandon] Yeah, I think it is. It's definitely harmful. I can see that in the people around me, because they're like, “Where's your contentment? Where's your satisfaction for what you’ve accomplished?”

[Annalee] Well, it's important to pause and appreciate it all. Because without this reflection, the challenges can feel so overwhelming. For every person that presents a challenge, there are probably ten others who are so happy to be a part of our endeavor, eager to learn from us. We have some real ride-or-dies. So, it's so important to appreciate these moments, despite the hardships. And I know it's hard. It's so much.

It all deserves space, I think. Making space for the gratitude as well as the desire to grow. I think people can get stuck in these binaries of… “If I focus on gratitude I will lose my drive,” or the opposite—that you should only be grateful and that desire is problematic.

[Annalee] Focusing on one doesn't solve the problem.

I have this tarot deck I love, and the King of Pentacles’ description speaks to this. It suggests that a part of our spiritual journey is understanding that longing never goes away, no matter how much you achieve. Instead of resisting it, we should embrace and befriend it. That acceptance becomes a destination in itself.

“I think now that I look back, I'm just like, wow. I was completely naive to the amount of responsibility I was in for.”

On another note, I never made the connection that you were at Bar Agricole. That means I've been enjoying your work way longer than I thought. Once, I even rented it out and produced a photoshoot for Google there. It was such a tech hotspot. This makes me wonder about the serendipitous paths in our lives, and how this is probably how you got acquainted with all of the wealthy individuals who ultimately invested in you.

[Brandon] It's true.

Can you tell me more about this chapter of your work prior to opening Mister Jiu’s?

[Brandon] At one point, I found myself at a crossroads. I had gathered significant training as a chef and had a burning desire to do something with Chinese cuisine. After training in Shanghai, I wanted to start something of my own. But, with limited knowledge on how to write a business plan or pitch it, all of my early attempts fizzled out. So I went back to cooking, hopping from one restaurant to another, always working under someone else's vision. While there was an element of freedom, there were also multiple layers of approval to navigate. It wasn’t what I imagined I’d be doing.

I longed for a job where I could fully express my creativity. As fate would have it, an opportunity at Bar Agricole came up, thanks to Melissa, a colleague from my time at Quince and our eventual opening pastry chef. They were trying out chefs, and she suggested they consider me. I seized the chance, bringing along two trusted friends to ensure the tryout went smoothly. Thinking back, it's remarkable considering the talent I brought: Thomas McNaughton from Flour + Water and Mike Gaines from Manresa. We delivered an eight-course meal that landed me the job.

Bar Agricole introduced me to the intricacies of opening a restaurant. Beyond just the food, I learned the importance of the full dining experience—from space ambiance to uniform design, table setting, and more. This was eye-opening. While I deeply valued the experience, I still wanted to open my own place and create Chinese cuisine. I had committed three years to Agricole, and upon its completion, I left to pursue my dream.

The transition wasn't easy. So many people I’d met over the years had expressed interest in investing, when push came to shove, it was silence. I couldn’t believe it. Not one person came through.

Those were challenging times. Financially, we were stretched thin, resorting to Airbnb-ing our apartment and retreating to her mom's place when it was booked. Relying on private chef gigs and the goodwill of my grandparents, who allowed me to stay in their basement apartment during tough times. We barely scraped by.

But Bar Agricole's success during the recession inspired me. Their unwavering commitment to their vision in the face of economic challenges instilled in me the perseverance to keep pushing forward. While it was a tumultuous period, it was also filled with incredible experiences, including the opportunity to cook for some truly remarkable individuals.

[Annalee] You should have seen us doing these gigs. Us in our little kitchen. We’d be washing greens in a tub on our couch. But these meals gave us access to so many amazing people and amazing ingredients, and while we had little, we ate well.

Make the most of what you have, right?

[Annalee] Yeah. And, they were all like really sweet people too. So generous.

[Brandon] Yeah. And then the Chinatown space that ultimately became Mister Jiu’s—it just came up randomly. So I put an offer on the space.

Did you have investment by this point? Like, did you manage to convert anyone?

[Brandon] Yeah.

What flipped it, do you think?

[Brandon] I was in fundraising mode right up to the very end, exhausting every available resource. Whether it was taking out loans or providing personal guarantees, I was determined to get whatever funds I could. At one point, the vision was to use the funds for both floors of our establishment. But two and a half years into the journey, we could only raise enough money to do the bottom floor. So what’s what we did. Moongate came much later.

I can definitely relate to what you guys are saying. I had an amazing network in Silicon Valley—I was friends with so many investors and high net worth individuals. And I couldn’t get a single person I knew to write me a check when I started Haus. I pitched for six months straight and not a single yes. It took me signing on the best branding agency at the time. And then suddenly people started showing interest.

[Brandon] What agency was that?

At the time, it was Gin Lane—they were behind brands like Warby Parker, Harry’s, Sweetgreen, and Hims. They had a knack for minting billion-dollar DTC brands. And they were obviously picky about who they worked with, because they could be. Getting them to take you as a client was the ultimate endorsement.

So yeah, fundraising was impossible for me. Then, I read Gucci Mane's autobiography. I grew up in the south and I was raised on hip hop, so I wanted to read the book, but I didn’t realize it would have such a big impact on my business. Gucci writes that during your first album, nobody really cares about you. It's all about your collaborators—the guest artists and producers, that sort of thing. It made me think, “who is my T-Pain?”

I realized a brand collabor might be the key. I had a really clear vision for the brand. If I could get the best agency in the game to work on it, that might be the missing piece. So, I reached out to Gin Lane via their website.

I quickly got a “no” back. But I was determined. So I posted on Facebook, trying to find a direct connection to Gin Lane's founder. Luckily, a friend responded and said he had attended college with one of the founders. I managed to score a 20-minute pitch with him he was walking his dog, and by the end, he was on board.

[Brandon] Wow. Hustle.

I had zero dollars when I signed the contract. But the minute I could say “Gin Lane-backed startup” in my email subject lines, everyone started responding to me. Everyone took a meeting with me. I managed to raise just enough to pay the first invoice.

I just kept doing that over and over. Potential investors kept setting new benchmarks for me. “Show us the digital prototypes.” I’d do that, and manage to raise a little more, which I’d send right to Gin Lane. “Show us the physical bottle. Show us the website mockups.” I’d do that, get some more money, send it to Gin Lane. Each milestone allowed me to gather just enough capital to move to the next phase.

Like you guys, I had to constantly adjust my expectations. Any ideas I had about how fundraising would go were all wrong. I had to operate on blind faith, just focusing on each immediate step, trusting that if I kept going, the money would somehow materialize.

[Brandon] It's a wild process.

It's insane.

[Brandon] So insane.

Looking back, I don't know if I could ever do that again.

[Brandon] I couldn't. I couldn't.

It took so much naivete and survival drive and blind faith. And a lot of “Fuck you all for doubting me, I'm going to do this.”

[Brandon] You know.

[Annalee] Oh, we were so stressed about how it was going to work. How we were going to get the money. You know? We were like, “We really have no idea, but we're going to do it.”

And as we’ve seen, it can eventually happen. We're very fortunate to live in a place where there's so much money. You get better at pitching and you figure out the social dynamics. You know, how every investor follows each other. And you figure out the game. But boy, it's one step at a time.

[Brandon] It is. Yeah.

I get exhausted just thinking about it.

“Whether it was taking out loans or providing personal guarantees, I was determined to get whatever funds I could.”

[Brandon] The fundraising journey was a rollercoaster I wouldn't want to experience again. After securing funds, we dove into the whirlwind of opening Mister Jiu’s. But even once we got the restaurant open and operational, there was still the task of raising funds for the upstairs portion. The fundraising never truly ended.

And your launch was a huge success by most people’s standards. And then comes the new unique hardships that come with being successful. Unsavory characters that want a piece of your pie, that sort of thing. Those were the challenges I really was not prepared for. Are there any of those stories you are willing to share?

[Brandon] Yeah, yeah, yeah. Unfortunately. The most memorable was with the general contractor for Moongate, the lounge upstairs that we built after opening the first floor.

[Annalee] That is its own chapter.

[Brandon] Oh my God. Yeah. So much money lost. And that money was like, so hard to come by. Watching it all get spent by a team of people that didn't give a fuck—it sucked most of the life out of me.

Right. Because you're like, “you don't even know how valuable this money is.”

[Brandon] We nearly ended up in court, and just getting close to that step was financially draining. It was a harsh wake-up call about how the legal system can be skewed. If someone has deeper pockets, they can easily outspend and wear you down, regardless of the case's actual merits. Our lawyers advised against pursuing the matter, pointing out the likely costs versus the potential return. These experiences have been hard lessons, and I'm still navigating the complexities of whom to do business with and how to approach it. How to not end up working with the wrong people.

I still don’t trust myself to do this well. I got it really wrong a few times. For a long time I felt so much shame over this. I felt like such an idiot.

But now, I've come to see this naivety as a virtue that I’d like to keep to some degree. I often operate under the assumption that people are morally upright, and I've been burned because of it. But I've also observed that those who operate with questionable ethics often believe everyone else is just like them. That feels like a bigger curse. So, after all these experiences, I've realized I'd rather remain somewhat naive or optimistic and occasionally getting taken advantage of, than become jaded and wary of everyone around me.

While it might lead to bumps along the way, I'd prefer to continue gravitating towards those with good intentions rather than expecting the worst of everyone.

[Brandon] I mean, I've had that energy for a little while—where I was really guarded. It's just really hard to trust.

Me too. And that's fair.

[Brandon] Yeah. Yeah.

[Annalee] It can be so much.

I think business owners are perceived as a person of power. And everybody in the world thinks they're punching up when they’re causing others harm. So if you're in a position of power, we're just going to get messed with from time to time. So we have to just come to peace with that.

[Brandon] Yeah.

“For restaurants like ours, there's this constant assessment: given how much longer our lease is and how far away we are from repaying our investors, is it worth it to stay open?”

Now I’d like to talk about the actual business of running a restaurant. Many people might not realize the challenges involved in running a restaurant, especially one that caters to a high-end clientele. While the clientele might have significant wealth, the economics of a restaurant are far more complex than just the ticket price of a meal. Expenses like rent, salaries, ingredients, and overhead can be extremely high, especially in cities or upscale areas. Plus, maintaining a certain level of quality and experience comes at a cost.

[Annalee] Oh for sure. People think “Oh, it looks nice. And this, like, has a luxury feel. So you must be swimming in cash.”

Yeah, yeah. You must be super rich. So I'd love to gain an insight into the restaurant business, especially one of your caliber. Given that this audience is primarily founders, could you provide a snapshot of your business model?

[Brandon] Restaurants typically have a profit margin between 5% to 10%. When you consider borrowing a substantial amount, such as two and a half million dollars to construct the restaurant, it can take several years, like four in our case, to pay back those investors. As of now, I haven't fully reimbursed my investors.

Can you talk about that for a second. Are you actively paying off investors with your profits? Did you have, like, a five year window in which you didn't have to pay? Like, what does an investment structure look like for a restaurant like yours?

[Brandon] It might be different in the current climate, but in terms of what operators offer to investors, during tougher fundraising periods, there's likely more incentive provided by operators to entice investors. This could include certain perks and benefits. Given the competitive landscape when I was establishing my business, the anticipated return on investment was a three-year payback.

Whoa. That sounds aggressive.

[Brandon] Yeah. In the best-case scenario, our projections aimed for a three-year payback. But these were goals, and not strict expectations. For the first couple of years, much of our profits were reinvested into ventures like building Moongate. I only began sending distributions to investors around 2018 and 2019. I was optimistic about maintaining this trend for another year or two, potentially reaching a point where our debts to investors were settled. But then the pandemic hit, plunging us into survival mode for three years. For restaurants like ours, there's this constant assessment: given how much longer our lease is and how far away we are from repaying our investors, is it worth it to stay open?

Sure. Is it worth the struggle.

[Brandon] If I can't ensure a return for our investors, it's challenging to justify staying in the game. In our industry, at least, all of our distributions are directed to the investment group until they're fully compensated. Once that obligation is met, the distribution dynamic shifts. 60% is then allocated to our operating group and 40% to the investment group. This model provides our team with financial hope. Once the investors are repaid, it's our opportunity to generate a more significant income, ideally stabilizing our financial situation.

[Annalee] That really is the payoff of our sacrifices. That’s our ultimate finish line.

[Brandon] And so when we talk about success, like, that's the one thing hanging over me right now—in my mind, we’re not there until I pay off investors. Like, I don't feel even of all the accolades. Like there's still that crucial part of the restaurant being successful that I have not experienced yet and I'm still wanting to achieve.

People don’t realize that even glamorized founders are still just still running business and often still trying to figure out how to be financially stable themselves.

[Brandon] Regarding the internal finances of a restaurant, I've been managing numbers even before I was running my own business. I've seen what goals were set in those restaurants, especially in terms of expectations as a kitchen manager. Typically, prime cost combines your labor and cost of goods. Ideally, it should be around 65%. However, while we aim to keep labor costs around 35%, it's challenging, and realistically, right now you're looking at figures closer to 45%.

Oh my gosh. I’m sure prior to the pandemic, no one would have believed that it's possible to work with that number.

[Brandon] No. And now, customers often notice rising prices, but it’s just a reflection of the rise both in cost of goods and labor. As I've learned over time, it's vital to have excellent people in every position and ensure they feel valued and well-compensated. Providing a professional structure within the restaurant comes with its own costs.

While the journey to financial stability is taking longer than I anticipated, I remain optimistic about reaching that goal eventually.

You did survive the worst.

[Brandon] Yeah. It's like, when you think your day can't get any worse, you remember that yeah, it really can. And if it does again, I won't stick around.

But it's hard. I mean I'm sure you guys have some PTSD from it—literally and figuratively. It's hard not to have your nervous system still adjusted to that time.

[Annalee] We went from managing a crazy, amazing team of 70 people to running the restaurant with six people.

Jesus. Laying off a team like that is so fucking hard. As someone who's had to do layoffs myself, it's like, man. It's not that you can help it, but you're taking away people's livelihoods. I remember feeling like I just destroyed so many lives, even though I had no other choice.

[Brandon] Yeah.

[Annalee] It felt fulfilling to eventually bring so many people back to work. Balancing the management and direction of the team, ensuring the business ran smoothly, and then having a child in the midst of it all was a massive undertaking. On top of that, reopening the restaurant and introducing a new concept added to the challenges. It's been quite the journey.

Yeah, you're really doing it. You should be proud.

So from an outsider's perspective, there's a noticeable "chef hustle" emerging post-pandemic. We now see chefs as influencers with cookbooks, brand partnerships, and even product lines in grocery stores. And I don’t think this is out of ego—it was necessary.

I remember predicting in 2020 interviews that chefs would become the new celebrities. The pandemic forced restaurants to adapt, making them dive into the digital world and try brand strategies they might have dismissed before. The fragility of the industry during the pandemic meant that trying anything and everything became the way to survive.

[Brandon] Some of our decisions came again from that place of “What do we have to lose?” Especially when everything seemed to be falling apart. One of the main reasons we remained open was because of a long-time employee who's been with me for over a decade. She couldn't benefit from unemployment since she doesn't have the proper paperwork. While many were relying on unemployment, she couldn't. So, we had no choice but to persevere for her sake. We experimented with different strategies, some of which revealed potential alternative revenue streams. Perhaps this diversification comes from PTSD. After the pandemic, relying solely on the restaurant for stability seems risky. Even if these other ventures and projects are minor in scale, they do offer us a sense of security.

Yeah, totally.

[Brandon] And more people are willing to do collaborations, I think even for you guys at Haus to do a collaboration with us during the pandemic. Like, liquor brands don't do that. You know, I mean, like, they're not looking for restaurants or even chefs to really have those collaborations with.

I get what you're saying. It's like, this has pushed everybody to be more creative. Especially in profit-based businesses, the ones not venture backed or whatever. You have to be more creative. And I will say, as a consumer of all of this new media that's come out of restaurants, I find that it's a gift. Like, I love being able to experience these new forms of creativity. The books, the online content, the brand collaborations, the retail products. So to be able to see these different expressions come out of food is super cool. It just took some horrific circumstances and some creativity.

[Annalee] It also feels great to collaborate with someone you respect. It makes it fun. At the end of the day, we want to enjoy what we’re doing.

[Brandon] During the pandemic, we formed a close collaboration with Lord Stanley, which birthed the “Lord Jiu’s” concept. At a time when many of us felt isolated, this partnership brought a much-needed sense of community. When our restaurant had its doors shut, it felt like we were each stranded on individual islands, just trying to survive. But these collaborations bridged the gaps and showcased our desire to support each other. These joint ventures really brought us hope during the pandemic, reminding me that I wasn't navigating these challenges alone.

I think the pandemic really changed how everyone approached their work. Something happened to me and I think other people too. Pre-pandemic, all of us were a little naive, right? We thought the path to our goals was a little more linear. And then the pandemic showed us that things can happen that are inconceivable and totally outside of our control. So if the potential outcome is what was driving you, that can no longer be the case. It has to be about the work, or the lessons learned, or community, or something else you can control.

[Brandon] Yeah, I mean, a global pandemic was not on my radar of things that could shut the restaurant down.

Like a world altering event that changes society forever? Yeah.

[Brandon] I had to grapple with the reality that everything we'd worked for seemed to vanish overnight when we first shut the restaurant down. Initially, I was so angry and sad. We'd poured so much effort into reaching our goals, and it felt like we'd never truly reached our potential. But through this loss, I had an epiphany. I'd wrapped so much of my identity around being the chef and owner of Mister Jiu’s that I'd inadvertently overlooked other facets of who I am.

Losing the restaurant made me reevaluate my identity. I rediscovered the importance of my roles as a husband, father, brother, and son. It emphasized the significance of relationships outside the world of cuisine.

The restaurant won't last forever, and in hindsight, it shouldn't. As we strive to reopen and rejuvenate it, I'm sure it will evolve into something different from its original form. And when the time comes to end this chapter, I don't want it to be a drawn-out farewell. Strangely enough, I wish for the restaurant to reach its peak once more so we can depart on a high note.