On Building a Media Empire, Creating Your Own Lane, + Letting the Work Lead

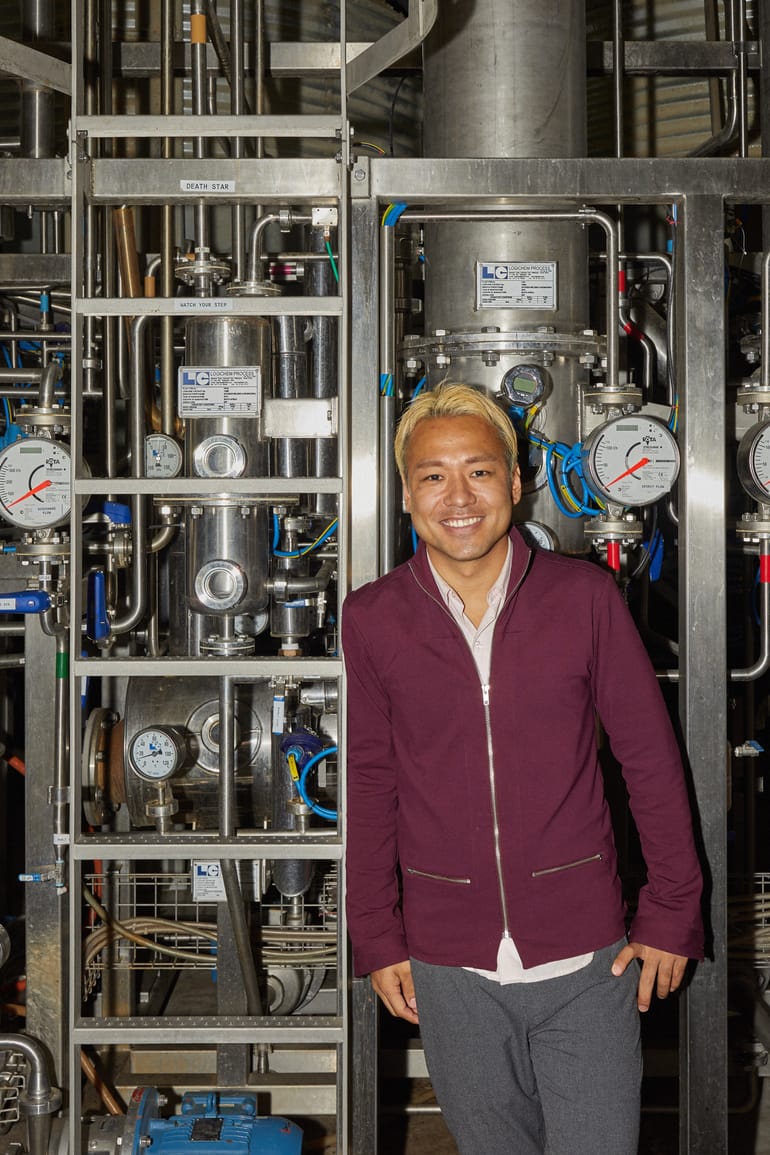

Dan Runcie is the founder of Trapital, a media company focused on the business of music, media, and culture. Dan started Trapital with a mission to elevate music, media, and culture, particularly by giving more in-depth and deserved coverage to business savvy moguls and executives.

Trapital has been featured in prominent publications like The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, BBC World News, NPR All Things Considered, and CNBC.

Dan's approach to covering the business of hip-hop is unique. He combines his deep interest in hip-hop, which began in his youth watching MTV and BET, with his business acumen developed during his time at the University of Michigan's business school. His insights into the industry are grounded in deep research and business analysis. This approach has resonated with many, and Trapital is now at over 30,000 email subscribers.

Dan offers weekly newsletters, monthly essays, and podcasts, featuring interviews with artists and business leaders in music and entertainment. He also invests in startups in the industry. These services, along with sponsorships for the newsletter and podcast, have created a diverse and successful business model, allowing Trapital to grow without outside investment.

Runcie has spoken at various events and institutions, including YouTube, SoundCloud, Sony, and the National Association of Black Journalists. His insights are sought after for their depth and relevance to current trends in digital media and the music industry.

I first met Dan on Twitter, where we were both doing a lot of tweeting at the time. I quickly dug into his work and realized I'd found an actual genius. The way he breaks things down, maps patterns and puts disparate pieces together for form an analysis—his content expands my mind in a way that most media does not. And because he's covering culture, you not only finish his work feeling smarter, you finish feeling cooler.

Interviewing him, I can see how he was born to do this work. He's been thinking this way since he was a kid, and he built his business in the same way he approaches his daily work—slowly, thoroughly, and ultimately, his way.

This breakdown of how Dan built his empire is great, and you should read it if you want to know some of the tactical details of how Dan built his media business.

Otherwise, enjoy our convo below.

H

Okay, we're recording. All right. Hey.

Thank you for having me.

I would love to start at the beginning. Where are you from? Tell me about your early years.

I was born in East Hartford, Connecticut, to parents who emigrated from Jamaica. My dad was a teenager when he came with his family, and my mom was in her early twenties when she arrived by herself. My older brother, who had spent his first nine years in Jamaica, came to the U.S. a few months before I was born. So, in many ways, we were all adapting to new things. My story, I think, shares a lot with that of a first-generation immigrant family—seeing things through their eyes, how they worked to assimilate, to provide the best for us, and learning from us too. For me, it was even more distinct being born here, starting from scratch as a citizen, which wasn't the case for my parents until later on.

I remember always being curious and inquisitive, asking questions my parents sometimes knew the answers to and sometimes didn’t. This curiosity seems common in immigrant upbringings. The year after I was born, my grandmother, my mom's mother, came up as well. She was more hesitant to assimilate, which was understandable given she was in her fifties. She wasn’t trying to navigate corporate America. She was one of my closest ties to life in Jamaica. We often visited as a family, and I enjoyed experiencing the multiple worlds I was a part of—understanding life in Jamaica, seeing my mom with her sisters, visiting Florida to see my dad's family, and then experiencing life as someone growing up in the U.S. on the East Coast. I definitely enjoyed it. It was still early, too early to think I’d end up where I am now, but I did enjoy those times.

I'm a kid of an immigrant too, and I'm curious—I feel like I see two paths in these scenarios when I’m talking to first-gen kids. Either their parents have this very specific idea of what they want their children to be, and they are really strict and hold them to it. Or there's kind of the opposite—like everybody is just trying to survive, so you have to figure out your own path without much guidance. Do you feel like one of those fit you better?

I think there was probably more of a push towards traditional careers, you know, like being a doctor or a lawyer. This is something a lot of immigrant families can relate to, wanting their kids to pursue those clear, esteemed paths. So, probably until high school, everyone thought I was going to be a doctor. Not because I had a passion for medicine or science, but it was more like, “Oh, I want to help people.” It sounds good when you say it, right? And it matched up with doing well academically, being in advanced placement classes and all that.

Okay, so you potentially have this more conventional future in front of you. What were your grade school years like? Looking back, can you see the beginnings of your life path starting to form?

Yeah, it was interesting. Early on, I was mostly following what I knew, what made sense, like wanting to be a doctor. But my brother, he was always clear about what he wanted. He was really into engineering and automotives, and he went into mechanical engineering. In our town, being the headquarters for Pratt & Whitney, many middle or working-class people with stable jobs worked there or at other United Technologies companies. It seemed like a path to consider.

But it was in later high school when I realized my interest in business and marketing, understanding how and why people buy products, how things are positioned. I was into all sorts of media—video games, movies, music—and always intrigued by store layouts, why things were placed where they were. I didn’t know the specifics but found it fascinating. Learning about things like the cost of advertising in the Super Bowl was eye-opening. It made me think about the expenses behind products in stores.

By the time I was 15 or 16, taking the PSATs and starting to think about majors, I knew I wanted to go into business. That's what I chose, and I followed that path through college and into my career, though the journey to where I am now was varied.

I mean, it strikes me as unique that you're that young and you are naturally drawn to connecting those dots when other kids might just be only playing video games. Where do you think that came from?

Sometimes, I think my interest in business partly came from my mom. She wasn't a marketer, but she was really into the culture of bargain shopping, which was very popular in the nineties. It reminds me of shows like “Supermarket Sweeps.” She would hunt for deals at outlet stores, always trying to find the best price. Even though I don’t shop the same way today, I learned a lot from that experience. I'd wonder why a product was half the price at an outlet store compared to what we saw in a newspaper ad or at Walmart. Being exposed to outlets and secondary resellers piqued my interest in understanding how businesses like these operate. Back then, I didn't know terms like “Arbitrage,” but it's clear now that these experiences shaped my interest.

For my mom, shopping was more than just a hobby—it was an extension of managing the home. Going shopping with her, I learned a lot about the business world without even realizing it at the time. I think that's where a lot of my interest originated.

“For my mom, shopping was more than just a hobby—it was an extension of managing the home. Going shopping with her, I learned a lot about the business world without even realizing it at the time.”

I just love when you can look back and spot a behavior in someone's younger years that ends up defining their life later.

It's interesting because now there's so many things that I look at with the work that I do now, whether it's why a record label would pay this much to try to sign this artist when I know that there's this other artist that they have that's a fraction of the price but can do just as much. But this artist may not get on Jimmy Fallon or may not get to host SNL, but they still put up numbers and why that exists in that type of way. I mean, that's essentially the same type of thing here.

Yeah. I mean, the phrase that keeps coming into my head is… “it's all business.” It took me a long time to understand that. I love that that was just natural to you from childhood—that you could see the “business” in everything.

Right. Yeah. It's fascinating. I mean, I guess I never actually thought of the connection that way. And it makes perfect sense. And even though the jobs I had before starting Trapital, while they weren’t directly related in that way, I think there's still certain aspects of them that at least interested me that I think make sense there.

Yeah, well, I want to talk about that. Walk me through your career path prior to starting Trapital.

So, I went to college with the main goal of studying business and marketing. I applied to schools mostly in the Northeast and ended up at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut. They had the degree I wanted, offered a good scholarship, and also had a five-year MBA program, which I thought I wanted to do. In the first year, like many others, I didn't quite focus on my grades and lost the scholarship. That hit me hard. It meant I was now paying out of pocket, so I had to get serious. I improved in school while still having fun, just being smarter about it.

That shift in attitude was significant for me. I realized I could control my destiny with hard work. Growing up, I had enough confidence to get into schools, play sports, but this idea of having no limits in what I could achieve didn't really hit me until college, when I saw the results of putting in the work. I remember discussing this with my wife recently. From kindergarten through elementary school, I was always at the top of my class. But in middle and high school, I slacked off, got distracted. The financial loss from the scholarship was a turning point. Once I started applying myself and saw the outcomes—better jobs, better responses, a change in how I felt and thought about things—I realized the more effort I put in, the better the results. This was a lesson I first truly understood in college and it has really helped me since.

That's so interesting, because I could see someone else having their scholarship taken away, and getting totally discouraged, and giving up.

And here you are, just seeing it as a new correlation that you didn’t see before. That feels like such a unique reaction for that age. As a late stage teenager just, you know, otherwise wanting to party and have fun and do teenager things. That you were able to react to that in a very different way than a lot of other teenagers would have reacted to that.

Right. It's like, when I was in college, I thought, “If I'm here, let's make the most of it. Let's work with what's in front of me.” And that approach has really served me well. But that doesn’t mean everything was easy afterward. There were times when I was thrust into new situations, each with its own learning curve. That's how it felt with my first job after school. When I graduated, it was the middle of the Great Recession, and jobs were hard to come by. Only a fraction of my classmates had jobs lined up at graduation, but I was one of them. I got a job at Travelers Insurance Company in their leadership development program for recent graduates. It was a competitive group, all pretty good from their classes and local schools. I enjoyed the social aspect and learned a lot from many brilliant people there. The insurance industry wasn’t my end goal, but it paid well, and I saw how people could progress there over ten years or so.

I knew I wanted to go to business school eventually. Back in college, a counselor advised me not to do the MBA program there but to work first and aim for a top-ten school later. That advice stayed with me. So, while at Travelers, about a year in, I took my GMAT, thinking I’d go to business school within five years. But a year and a half into the job, I decided it was time, earlier than expected. I got into Michigan, talked it over with my girlfriend, now wife, and she was open to the change. So, we did it, and it turned out to be two memorable and influential years that really opened up my world to what I could accomplish.

Do you feel like your drivers at that point in your life were more conventional—like, going up this business ladder, or were you also still really driven by understanding business and how the world works through that lens?

Yeah, definitely. I'd say so, because what I really enjoyed about the program was delving deep into various case studies, like discussing Disney's strategies in the early 2010s or analyzing companies like Ryanair or Southwest Airlines. Those discussions were fascinating. However, what really stood out to me was in my second year, about ten years ago. It was when Beyonce dropped her surprise album at the end of 2013. Harvard Business School wrote a case study on it just a few months later, and that caught my attention. It was innovative marketing happening in real-time. We had spent a year and a half studying legacy companies, but this was what we needed to focus on, especially for our future careers.

“What really stood out to me was in my second year, about ten years ago. It was when Beyonce dropped her surprise album at the end of 2013. Harvard Business School wrote a case study on it just a few months later, and that caught my attention.”

This case study stood out because of its uniqueness and the exposure and traction it gained. It was a lightbulb moment for me. I thought, “I've spent all this time learning to evaluate businesses, why not apply it to an area where I see a gap, something I'm personally interested in?” That's what got me started writing about the industry as a hobby, just to see where it would go.

Interesting. So did you feel a really strong, like an equivalent interest in the music industry at the time?

For me it was about the future, but it was also about what was happening in culture and the environment, things that I personally connected with. I've always loved music, hip hop, and pop, but I didn't see a clear career connection, especially in a business school environment. At that time, most of my classmates were aiming for jobs at Amazon or big management consulting firms. Music industry careers weren't really on the radar at my school, so I didn't give it much thought. I remember interviewing with Disney, but even that didn't seem like a direct path to a music-related career. It was more about exploring possibilities.

Another pivotal moment was during my internship at Delta Air Lines between school years. I remember overhearing a conversation between two employees who were identifying planes by type just by looking at them from the headquarters next to the airport. Their enthusiasm and knowledge struck me. I realized I wanted to be in a field where I could have that level of passion and excitement, to really dive deep into something I care about. I didn't feel that way about insurance or at Delta because I couldn't imagine having such a conversation about planes. It made me think about what truly aligns with my interests and how to pursue that path.

Walk me through the early stages of what became Trapital.

Yeah, so a few things happened after I graduated. I moved to San Francisco and started interning at what's now Reach Capital, a venture philanthropy firm doing edtech investments. This was my intro to San Francisco, and it kind of demystified the startup world for me. Back East, starting a company seemed far-fetched, but here, it felt within reach.

After Reach, I also joined Education Superhighway, a nonprofit. I wasn't directly using my previous experience, but I learned a lot. I saw the company grow from about 20 to 80 employees, working in strategic partnerships, and figuring out how to make things work in a complex system.

Meanwhile, around 2015 or 2016, I started getting noticed for my Medium posts. I began freelancing for Wired and other publications. Seeing people like Ben Thompson succeed with newsletters got me thinking. I reached out to Substack early on and decided to launch Trapital as my own platform, focusing on music and hip hop. I wanted to tell the important stories in this space with a unique, fresh perspective.

The first Trapital newsletter went out in 2018, and by 2019, I went full-time with it. It's been an incredible journey, step by step, seeing how it's grown and evolved.

"That's stayed with me, this idea of letting the work lead."

I mean, and it's amazing to me that you weren't obsessively studying the business of hip hop since you were two years old because you seem to know everything.

It's interesting, now that I think about it, how my background kind of meshed into this story. I wasn't studying this stuff since I was a kid, but there were signs. I was that kid who grew up on BET, glued to the TV. Early on, I got into CD burning and became the go-to guy for music in school. I’d be like, “Hey, the new 50 Cent CD is out. Don’t sleep on it. I got it for $5 a week early.” I was on top of it.

Also, I had an iPod early on. I'd come home from school and spend hours curating iTunes playlists, making sure every track was tagged right. I'd buy blank CDs, make sure everything was labeled correctly, and then sell them like a product. It’s funny, looking back, how this was probably where it all started for me. I was also the guy everyone relied on for music at parties or in the car. My iPod was the go-to.

These experiences, being that music guy, having that entrepreneurial spirit even back in high school, they kind of laid the groundwork for where I am today. So, in a way, it all comes full circle. That early love for music and knack for curating and sharing it probably fed into the knowledge I have now.

All right, that makes more sense. When people ask you what you do, have you found it hard to explain what you do because you’ve carved such a unique niche for yourself?

Yeah. It's like when you meet someone, the second or third question is usually, “What do you do?” And yeah, I've definitely followed a nontraditional path, going from an insurance company to spending years at a nonprofit before this. On paper, it might look like a “what?” moment. But I believe the work speaks for itself. That's stayed with me, this idea of letting the work lead. It's about showcasing what's actually done, which in a way, is the crux of it, right? Letting the work speak for itself because that's what really matters in the end.

When did you feel like you got to that place, where the work was there and it spoke for itself and how you defined yourself didn't even matter?

It felt like a gradual realization. I started Trapital back in March 2018, and by around September or October, I was putting out weekly pieces. My list of subscribers was still small enough for me to notice the names signing up. And it struck me—I recognized some of these names. These were people I never expected to interact with, yet here they were, reading what I had to say on a regular basis. That was the first sign that I was reaching the right people.

“My list of subscribers was still small enough for me to notice the names signing up. And it struck me—I recognized some of these names. These were people I never expected to interact with, yet here they were, reading what I had to say on a regular basis. That was the first sign that I was reaching the right people.”

As more of these influential readers joined, it reinforced the feeling that I was on the right track. Then, when key decision-makers from major companies began reaching out, deeply engaged with my content, it was a whole new level of validation. They would share insights or confirm my thoughts, sometimes even mentioning that my articles were topics of discussion in their boardrooms. Hearing about that impact, especially so early on, was a real eye-opener. It was then that I knew I had to go all in on this. That was the moment I decided to save up and fully dedicate myself to this path.

Where did you find the courage to enter and own this space?

Yeah, I think there were two key aspects. First, there's the subject matter. It's about having the confidence to be exploratory yet assertive in what I’m saying and putting it out into the world. This balance is crucial for me. The second aspect is understanding how digital media works. I didn’t directly work in this field, so grasping the nuances of digital distribution was essential. I needed to figure out how to effectively use platforms like Twitter and LinkedIn, how they could amplify my work and impact the reach of my content. These were aspects I spent a fair amount of time thinking about.

"It's about having the confidence to be exploratory yet assertive in what I’m saying and putting it out into the world."

Can you share more about your process of learning and mastering the trade?

Yeah, it's a combination of things. I sort of categorize it in my mind. First, there are the skills I needed. I had to really understand the industry, which I was already writing about on Medium. Seeing the response to my articles, which I edited myself, gave me confidence. It made me think, “If this is good on its own, how much better could it be with a professional editor?”

Then there’s the digital media aspect. I needed to get a grip on that, so I reached out to various people for insights. I would ask someone with a huge following, “What's your secret? How did you make this work?” I took notes from other newsletter writers, from those at bigger companies like Morning Brew, trying to absorb as much as I could.

But I had to experiment—some advice worked, some didn’t. And when I started a podcast, that was a whole different ball game. I underestimated the amount of work it would be. It’s not just about repurposing content; it’s about creating something that truly engages. The successful podcasts are the ones where the creators are fully invested.

Navigating this new medium meant adjusting my approach, focusing my energy where it mattered. It’s been about learning from others, yes, but also about understanding that not every playbook out there applies to your situation. The digital landscape is always evolving.

"It’s been about learning from others, yes, but also about understanding that not every playbook out there applies to your situation."

So you’ve been doing this for five years now. That’s a lifetime in startup years.

Right. The longest job I've had at this point.

And like, look at the landscape now, right? Everybody wants to become a solopreneur media tycoon, right? What do you think about that? Is there room?

The industry you're in really matters, right? I've come to realize this, sometimes frustratingly, when reading about the creative economy online. There's often this narrative that if you dive deep into a niche, there's a huge opportunity waiting for you. Like every subreddit is supposedly a billion-dollar opportunity. But that's just not how it works. You need to be in an industry where people are actually willing and able to pay.

“You need to be in an industry where people are actually willing and able to pay.”

Take my focus on music, and the broader media and entertainment sectors. These are areas ripe with disruption and change, sure, but they don't necessarily have the financial depth you might find in tech or finance. This reality has made me more conscious about how I approach my business model. It’s not just about having a great idea; it's about understanding the market, who your audience is, their spending capacity, and their willingness to invest in what you offer.

I feel lucky that things have panned out for me, but I know it's not just a walk in the park. Choosing the right industry matters, and even then, you need more than just good ideas. I think this is often glossed over in discussions about the creative economy and how to succeed in it.

Were there any other elements of building this business that were surprising to you, that you had to master?

I think understanding industry dynamics is key, especially in music and media. There's a lot of PR-driven coverage, which is different from other fields like sports. I realized this when I saw there was a gap in how things were being reported. For example, you rarely see straightforward headlines about record label executives being fired for incompetence anymore, unless there's some scandal involved. Understanding this helped me shape my media company to be honest and driven by genuine interest.

I learned a lot of this by talking to people who had been in the thick of it, those who worked at these companies. They gave me insights into how the industry really works. And then there's the learning aspect, like with podcasting. Initially, I managed to get big names for the podcast, which was great for credibility. My first guest was Matthew Knowles, Beyonce's father. But as I went on, I noticed a pattern with my listeners and even with my own listening habits. People often skip interviews just to hear the hosts talk. That led me to shift the podcast's focus to deeper, more regular conversations, similar to the deep dives in my newsletter that really caught on, like the one about J. Cole’s $1 concert strategy.

“I learned a lot of this by talking to people who had been in the thick of it, those who worked at these companies. They gave me insights into how the industry really works.”

Now, if I do an interview, it’s carefully chosen. I avoid repeating what other outlets are doing because that doesn’t add unique value to my platform. It's all about refining and adjusting to make sure the content stays relevant and engaging.

There’s something that strikes me about you, that feels somewhat unique to me today. I would describe you as someone who wants to analyze and get to the bottom of things, and ultimately share the truth. Separately, it seems that a lot of people online today equate truth telling with antagonizing. And you don't strike me as an antagonizer.

Well, thank you.

Yeah. And so I'm curious with you, because everybody can decide what path they want to take there, right? Every industry has its own issues and can improve in many ways. And I'm curious if you just kind of naturally landed where you are in terms of how you pursue and share your truth.

Right, you know? It's a good question and something I've pondered a lot. I'm less interested in pushing a specific agenda, even though there's a broader mission to elevate the industry. I've realized that elevation can happen through both positive and negative commentary. Critiquing, if honest, can be a learning opportunity for everyone. This approach is quite different from others in the field. When people have been let go from companies, I've addressed it directly, which has led to mixed responses. Some appreciate the honesty, while others, perhaps more fan-oriented, have been upset. But that's part of the job, and I believe it's crucial to maintain that honesty in our work.

I strive to be clear and balanced—praising where it’s due, but not searching for negativity where it doesn't exist. Over the years, some of my perspectives might have rubbed people the wrong way, but at its core, my work stands for what it is, and I'm proud of that. I've heard from industry leaders who value what I do precisely because I address issues others might shy away from. This feedback reinforces my commitment to calling things out when necessary.

For instance, during the peak of Web3 discussions, everyone was talking about it non-stop. But my approach was to not just jump on the bandwagon but to critically assess and discuss it in a way that added real value and perspective.

Where do you find your drive comes from today? Do you have the same motivations for why you do this work now than in the beginning, especially now that you make a full time living from it?

That's a good question. If I think about it overall, no, not much has changed for me. I'm still driven by that same desire to find and share unique stories, to stand out with something meaningful. It's this combination of curiosity and a deep understanding of the business that keeps me going. Highlighting key industry points, whether they're popular or not, is still at the core of my work.

“It's this combination of curiosity and a deep understanding of the business that keeps me going.”

Of course, life's different now. I’m not just living off bonus money with a year to figure things out. There’s more at stake with two kids and a family to support. It’s changed how I operate to some extent. I've found new ways to make the business work, like doing more in-person events and being smarter about our offerings. But these are just tactical shifts; they don't change the overall mission of my work or how I approach it. Elevating and supporting the industry remains my primary goal, and I'm thankful we've been able to do that.

The journey has brought unexpected turns, like venturing into angel investing with Trapital. It wasn't part of the original plan, but it made sense as the business evolved. It's been rewarding, despite the challenges. In many ways, running my own business feels more stable than a traditional job. I've built a network and resources that provide a safety net, which is reassuring. And if anything ever happened, there are now more opportunities for me to use my skills elsewhere. But I'm committed to this path. I love what I do and plan to keep at it for as long as I can, hopefully until I retire.

It feels like you are doing what you are absolutely meant to do.

Yeah, yeah, it can be pretty wild sometimes. Listening to how other companies or people talk about building their businesses, their strategies for monetization—it's enlightening. Not that I’m arrogant enough to think I know it all—I certainly don't. But I rarely come across ideas that are completely new to me. After all this time, I feel like I've heard almost everything that could be done with a platform like mine. I’ve spent so much time thinking about what works for my business, more than anyone else possibly could from their perspective.

On the flip side, I often hear from industry insiders who tell me they think I understand their business better than they do. I wouldn’t go as far as to claim that myself, but I get why they might think that. Having had numerous conversations with these folks, understanding their mindset both on and off the record, gives me a unique vantage point. It's a valuable position to be in, and I believe these insights are what compound over time to enhance the output of my work, at least in my opinion.

I also like hearing stories about companies that are bootstrapped and profitable. It was not long ago where taking about profitability in Silicon Valley felt scandalous. Definitely for early stage.

Yeah, you know.

I can attest to it myself. I remember even having employees myself that didn't understand when I would bring up the idea of profitability. But there was a long time where the business side of startups did not matter at all in the early stages. So it’s kind of understandable that employees felt this way, because that’s what they’d been taught previously in Silicon Valley.

So I actually think this is kind of an important thing to talk about. That you can build our dream company, in a niche of your own, being innovative, benefitting your community, and also being profitable, at scale. And that is enough. You don’t need the exit.

Right?

I think that is antithetical to how Silicon Valley has thought about things.

Yeah.

And I think that there is a big population that's coming from Silicon Valley. They are going to enter a new chapter at some point, whether it's now or later. And they're going to have to unlearn that.

Right? Yeah. There's this focus on what's the most financially viable way to build something. It's like going wherever the wind blows. And sure, we're not running non-profits here, which have their own challenges, but there's a distinct element to my approach. It's more than just financial outcomes. If it were only about money, I could have taken a job at a big tech company and ridden that wave. But that's not what this is about.

“It's more than just financial outcomes. If it were only about money, I could have taken a job at a big tech company and ridden that wave. But that's not what this is about.”

I recognized there was more to it—a purpose and drive that went beyond just financial success. That's why I've chosen not to take outside investment for my media company. When I looked at the media business landscape, especially those driven by sponsorships, the multiples weren't exceptionally high. So, I saw more value in the access and opportunities my platform provided, which allowed me to invest on my own terms. That approach has been more rewarding than simply aiming to sell the business.

Building my business this way means I don't have a traditional boss to answer to, but that doesn't mean I don't have accountability. I work with large partners and sponsors, and there's a significant level of engagement and responsibility involved in these relationships. So, it's not the freedom from accountability that some might imagine when you're a founder. For me, choosing this path was about building something that aligned with my vision and goals, not just pursuing a conventional route to business success.

Your business has expanded into multiple areas, and multiple ways for you to generate income and personal fulfillment. This is also something I want to highlight for founders—that you don’t have to put all of your eggs in one basket, that you can derive different benefits from different baskets. Can you share more about how you do this?

Right? Yeah. Looking back at my previous jobs before going full-time with Trapital, there’s a lot I reflect on. I used to travel often for work. Ironically, it wasn’t the travel itself I enjoyed—the flights, the delays, staying in hotels. It was about meeting clients, representing my company, feeling like we were planning and building something together. That experience, in many ways, helped offset the frustrating office politics. There was a balance that made it worthwhile. It makes me think, “What keeps you in a job?” In a way, I’ve found similar elements in my current role.

With the sponsorship side of the business being solid enough to fund operations and be profitable, I recognized there was room to grow. Adding in-person events, considering the long-term potential of investing—these were steps to elevate the business. It’s not just about making money—there's a strategy and a need for discipline in decision-making. The flexibility I have now has opened up really cool opportunities, even if they’re not the most lucrative. They help expand the business in other ways.

For instance, I’ve done several speaking engagements, like one at Stanford, which I really enjoyed. I've received offers from people who've seen my talks or clips online and want to collaborate on projects. The podcast also plays a crucial role, serving as a beacon that attracts these opportunities. People hear the episodes, get a feel for my expertise, and reach out for other things.

The analytics show the impact—thousands of downloads, being top 1% on Spotify’s most downloaded charts. It’s a reminder that the content is reaching key decision-makers in the industry, leading to more opportunities. Managing a media property is definitely a grind, requiring consistency and more than just putting out episodes. But it's the longevity and the build-up over time that really pays off. I still feel like I'm in the early stages, but these elements help in continuing to build and grow the business.

When did you realize you needed support, and how did that come together?

Getting the right support is crucial, especially for the more time-consuming tasks that I don’t necessarily need to do myself. Like anyone who's built a company knows, in areas like writing or podcasting, the creative part is mine—the thinking, recording the episode—but there are other aspects where I can use help. Research assistance, editing episodes, handling production so everything's ready to post—delegating these tasks saves me a lot of time. I hire people, whether part-time or on contract, to handle these things, like an assistant for specific tasks, especially for in-person events like coordinating with venues, handling travel arrangements, and so on.

This approach allows me to focus on what I do best. I'm most energetic in the mornings, so that's when I tackle the most crucial tasks. My weeks usually start off intense and wind down towards the end, so I plan my schedule accordingly. Having control over my schedule means I can design it to work for me, but I also know I can’t do everything alone. Keeping the team lean is important to me—I don't want to expand more than necessary, but I also ensure fair compensation for everyone involved. This balance has worked well so far.

And yes, it's still a lot of work. My wife often points out that I’d probably be busy no matter what I was doing, and she’s right. She knows me well, so I value and try to follow her advice quite a bit.

Cool. And, you know, I don't know if I've even said this to you directly, but I've read all kinds of business media over the last 15 years and I learn more about business from your stuff than most other things.

Thank you.

I say that for anyone reading here—even if you’re not an avid hip hop fan, you will absolutely take away valuable lessons and inspiration from Dan’s work.

For those readers out there wanting to start something of their own—would you have any thoughts or advice for them?

Thinking about what you naturally gravitate towards and have an interest in is crucial. It's not just about pursuing your “passion”—sometimes that word is overused. It's more about those areas that you find yourself consistently drawn to, where ideas seem to flow effortlessly. This is often where your best ideas emerge, during routine activities like a run, when your mind is at ease. The key is to start small and not put too much pressure on yourself. When I started Trapital, I had modest goals and expectations. You don’t need to add unnecessary pressure at the beginning. It's important to allow yourself the freedom to explore and see where things naturally lead, rather than sticking rigidly to a set plan.

“The key is to start small and not put too much pressure on yourself.”

In the early stages of Trapital, I began with bi-weekly newsletters, closely observing what resonated with my audience. It was a specific piece that really took off and reshaped my thinking. It highlighted the need for more stories of a similar nature. This experience taught me the importance of being adaptable and open to change. It's about balancing a sense of direction with the flexibility to pivot based on feedback and new insights. This constant process of iteration and adaptability has been a significant factor in my journey. Now, five years in, I can appreciate the growth and progress, a testament to this approach of organic development and responsiveness to opportunities as they arise.

Yeah. All right. Last question. How can the outside world support you?

If someone reading this is interested in the kind of content we're talking about, then absolutely, I think they should listen to the podcast and sign up for the newsletter. And if they're already a follower, sharing it with a friend is a great way to help us reach more of the right people. This isn't just for music industry decision-makers—it's for anyone trying to connect their brand or company with an audience. They're always looking to partner with the right people, to craft the right messaging, and I believe our content, especially the latest podcast episodes and newsletters, really hits the mark. It's the operators, investors, and key players in the space who will find this particularly valuable. Spreading the word about these insights is the best way to extend our reach and impact.