On Embracing Insecurity, Learning Everything You Can, and Building Employee Culture

Julie Zhuo is best known as one of Silicon Valley's top product design executives, as well as an expert and bestselling author on management.

Immigrating to the U.S. just before she was six, Zhuo's early life was shaped by the high expectations of her immigrant parents and the unique pressures of being an only child under China's one-child policy.

Zhuo eventually found herself at Stanford University, where she began to carve her own path in computer science. This led her to join Facebook as an engineering intern when the company had fewer than 100 employees. She eventually worked her way from intern to VP of Product Design. She remained at Facebook for 14 years.

Throughout her career, Zhuo has navigated the complexities of being in the "gray space"—not fitting neatly into the roles of engineer or designer but finding her unique strength in bridging these disciplines. This journey of growth and self-discovery eventually culminated in the publication of her bestselling management book, The Making of a Manager: What to Do When Everyone Looks to You. Drawing from her own path and deep research, Zhuo shares how effective leadership evolves through experience, feedback, and a commitment to growth.

Zhuo's insights into leadership, design, and technology have been featured in major publications like The New York Times, Forbes, and Wired. She has spoken at leading tech and design conferences worldwide, and she has appeared on many prominent business and leadership podcasts, where she delves into the themes of her book and her vision for effective and compassionate leadership.

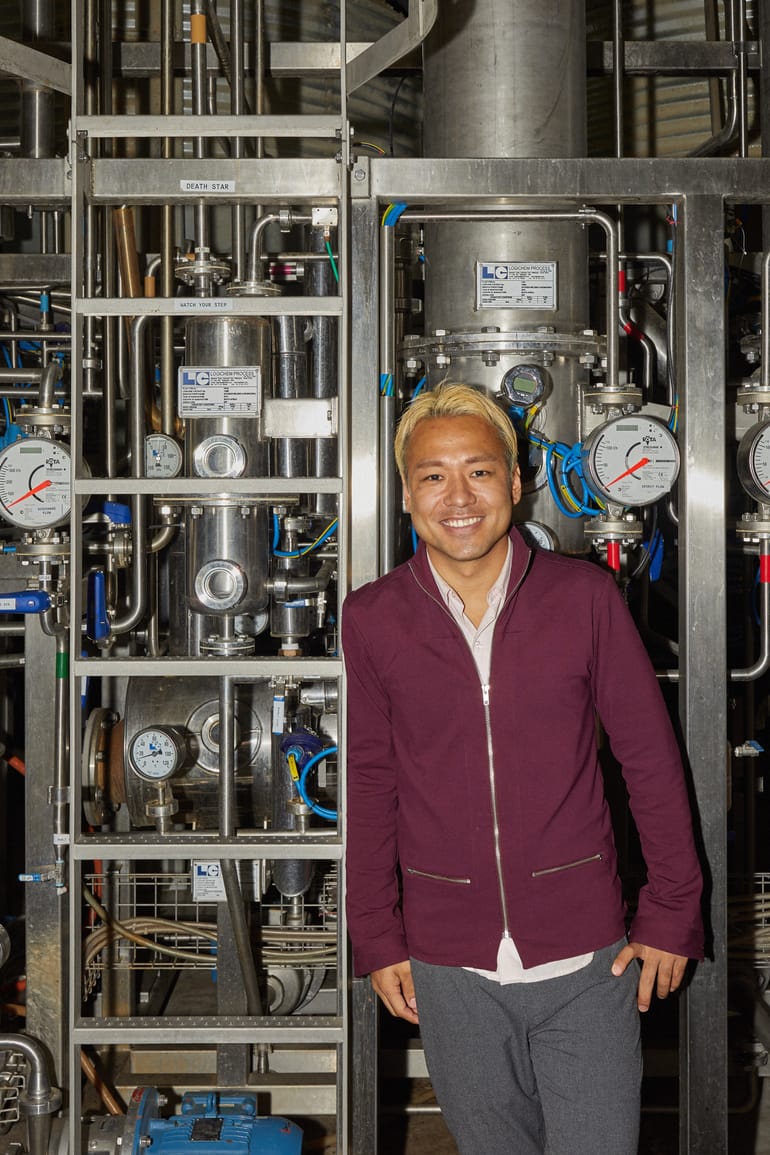

Today, Zhuo is a co-founder of Sundial, applying her experience to the challenges of making data accessible and actionable across teams. She manages a remote team of over 30 employees, and her clients include many of your favorite technology companies. She continue to share her writing via her newsletter, The Looking Glass, to over 70,000 subscribers.

This chat with Julie was over two hours long, and could have continued for hours more. I hope you enjoy reading it.

H

Hello Julie.

Hi.

Thank you so much for having this conversation with me.

So I generally like to start at the beginning with people. Different subjects tend to have different areas of their early life that were impactful, and unique to them. And, knowing some of your story, what often comes up is your early career path.

You joined Facebook when it was sub-100 employees as an intern and became, from what I understand, either the youngest or one of the youngest managers, and worked your way up to VP of Product Design. Arguably one of the most powerful tech positions in the world at the time.

And so I'd love to talk about that experience, but if you’d like to start earlier, then let’s go there.

Yeah, so, a bit of my background—I immigrated to the U.S. when I was six. I was raised by what you'd call 'tiger' Asian parents, and being an only child, thanks to China's one-child policy, had its unique pressures. My dad, especially, was always looking for a way out of China. Having grown up during the Cultural Revolution, he's always been the academic type at heart, passionate about learning. It was particularly tough for him, with schools being scarce and him having to pursue knowledge covertly, delving into books and subjects that weren't exactly sanctioned at the time.

My dad really couldn’t stand the government back home. He was always looking for the slightest chance to bolt. Once things eased up and he could go to university, he was all in, constantly scheming to get out of the country. He’d soaked up all this stuff about America, democracy, and was super against communism. He managed to snag this opportunity to leave, but here’s the kicker—when he married my mom, she had no clue about this big dream of his. Imagine that, right? They tied the knot, and then he’s like, “Oh, by the way, I’m planning to get us out of here.”

And so, my parents came over, and they actually left me behind while they went through their bachelor's degrees. So, I grew up with my grandmother and my uncle until I was six before coming over. I mention this because it feels like a common narrative among Chinese immigrants of that generation. This story, the one I was told growing up, was all about how I am my parents' hope and dream. The reason they strove to provide a better future for me. Being an only child meant all their resources and sacrifices were focused on me. And with that, I always felt this expectation to grow up and make something significant of myself.

"Being an only child meant all their resources and sacrifices were focused on me. And with that, I always felt this expectation to grow up and make something significant of myself."

So, I often think about where my ambition or drive comes from, especially now that I'm a parent myself with my own kids. It's like, this story is where it all begins. The whole idea was ingrained in me from the start. My parents, they didn't exactly aim for the stars for me—they were more like, “Get a good job, maybe a doctor or a lawyer, just something stable.” They wanted me to be comfortable, not lacking anything. But yeah, the expectation was clear: get good grades, do whatever it takes to secure a steady, stable income.

By my teenage years, the narrative was so embedded in my mind, it had become my own story. I took pride in the idea that I was going to achieve something significant, fulfill my parents' dreams, and make the most of being in America. But there's also this other part of me that felt like an outsider, a feeling that's probably familiar to many immigrants. Balancing different cultures, I often felt like I didn't quite belong, always observing what was happening around me because I never felt completely at ease, as if this was exactly where I was supposed to be.

So I ended up studying computer science, which was my way of rebelling, I guess. You know how every kid has their rebellion story? Mine was deciding not to become a doctor or a lawyer, which is what my parents really wanted. But I couldn’t just ignore their expectations completely, so I chose the third option on their list—engineering. However, I wasn’t about to be just any engineer. Thanks to discovering the internet back in middle school, I got really into web development. It felt like my own way of choosing a path, but still on my terms.

So, I was set on studying computer science, and eventually went to Stanford. In my senior year, I got into this program called the Mayfield Fellows. It's this thing for juniors and seniors that really throws you into what Silicon Valley is all about. The program lasts about nine months, with a spring course, a summer internship at a startup, followed by a fall reflection course. The spring part was sort of like a Silicon Valley mini-MBA. We dove into case studies of startups, listening to VCs, operators, CEOs, and founders share insights on their experiences. And part of the deal was to land an internship with a startup. They had this vast network, giving us a chance to connect and talk to people in the industry.

I actually interviewed with Sam Altman's startup at the time, Loopt, for the program. One of my mentors was working there, which is how I got the interview. But deep down, I already knew I wanted to go to Facebook. The main reason? A bunch of my friends who had graduated a year or two before me had landed jobs there. Before, Google was the place to be, and a lot of Computer Science and Engineering grads were heading to Microsoft, Google, or various startups. Palantir was also recruiting heavily. But Facebook was this new, exciting product we all used in school.

My interview day at Facebook was chaos—nobody seemed ready for me. I had to tap an engineer on the shoulder and say, “Hey, I’m here for my interview.” I got back, “Oh, right, go talk to that person.” All of my interviewers were late. What blew my mind the most was that not a single coding question came up. It was so informal. Boz, one of my interviewers, pulled out a 3D puzzle with metal skyscrapers and said: “Solve this.” I’m thinking, “What does this have to do with my engineering skills?” But I went with it. And that was it, really. Everyone threw high-level questions at me. Coming from a background of more structured interviews, this was a shock. It really highlighted how early-stage and unstructured Facebook was back then. I felt they took a leap of faith with me, and I with them. Somehow, it worked.

"My interview day at Facebook was chaos—nobody seemed ready for me. I had to tap an engineer on the shoulder and say, 'Hey, I’m here for my interview.' I got back, 'Oh, right, go talk to that person.'”

So, I jumped in, starting as an engineering intern. Compared to my time at Microsoft the year before, Facebook was a whole different world. At Microsoft, I found myself constantly checking the clock, wondering if it was close to quitting time yet. It felt like there was this massive, overwhelming structure, but not much was really expected of me as an intern—it was more about being there, getting the “Microsoft experience.” It made me question if that was what the real world was supposed to be like, just watching the clock and waiting for the day to end.

But at Facebook, it was nothing like that. Within the first few weeks, I noticed I wasn’t watching the time. It was a stark contrast to the structured environment at Microsoft. Facebook had its own vibe, where the days seemed to fly by without me even thinking about when they might end.

I found myself staying late at Facebook, mainly because it felt like college. It reminded me of working on group projects at Sweet Hall, the old building on Stanford Campus with unix terminals where computer science students would work all hours of the day. The atmosphere was buzzing, filled with either college dropouts or recent grads like myself, making everything feel dynamic and fresh. Daft Punk always played in the background. I loved that energy. Even though I was figuring things out as I went along, the startup vibe was infectious. We were encouraged to “just ship it” from day one. Encountered a bug? No problem—fix it and ship it again. That hands-on, fast-paced environment was what drew me in and made me decide to stick around. It was all about diving in, making things happen, and learning on the fly.

Just three weeks in, I was all in. I found myself asking, “So, when can I get a full-time offer?” It reached a point where, after a few weeks, I was thinking, “I could keep doing this internship, but why not just commit?” Sure, I had a few classes left to finish, but I was ready to juggle those with a full-time role if they’d offer me one. And that’s exactly what we did.

I didn’t know much about design when I started—I was purely an engineer. On my first day, they paired me up with Ruchi, the only other female engineer at the time, like a “you’re a female engineer, go talk to that female engineer” kind of thing. The first thing she tells me is, “I don’t have time to be your mentor, I’m switching roles. What area of engineering are you interested in?” So, I mentioned my interest in front-end development—working on the part of websites that people interact with, since that’s what I enjoyed doing. She was like, “Cool, why don’t you hang out with the design team? They can show you the ropes.” And just like that, she introduced me to the designers, leaving me to learn from them.

I noticed there were about 5 or 6 designers already, and I was like, “Oh, a designer. What’s that?" It turns out, at that time, being a designer at Facebook meant not just working on designs in Photoshop—which I was somewhat familiar with from doing digital illustrations—but also coding the front end, like JavaScript, PHP, and CSS. And I’m like, “I can do that.” So, that’s how I ended up sitting with the design team. Over time, I started blending in, but this really ties back to how I’ve always viewed myself as an outsider. Even within the design team, for years, I felt like that outsider—the engineer among designers, without a real background in design, clueless about things like typography or colors.

Yeah, that pretty much sums up how I felt back then—I was like this front-end engineer who didn’t really know much about design. Honestly, I felt like I was pretty bad at design, especially compared to the talent around me. To make up for it, I focused on coding, trying to bridge that gap between me and the average designer. But when I compared myself to the engineers, I felt outclassed there too. We were bringing in some incredibly skilled people, folks who’d been coding and working on their own projects for years. I found myself in this weird middle ground, not quite fitting in with the engineers or the designers. I wasn’t as skilled in engineering as my peers, nor was I as adept in design. I was stuck somewhere in between.

"I found myself in this weird middle ground, not quite fitting in with the engineers or the designers. I wasn’t as skilled in engineering as my peers, nor was I as adept in design. I was stuck somewhere in between."

You know, this reminds me of an interview I did with John Maeda for Techies in 2016. We talked about the “gray space”—this in-between space where disparate perspectives and disciplines are blended—and how it relates to creation. The gray space makes most people uncomfortable because we all tend to be binary thinkers and we don’t like the in-between. And I also think in Silicon Valley in particular, it started as such a specialization culture and maybe remains one. But like, that's kind of core to Silicon Valley culture—like, “oh, you’re an engineer? What kind of engineer?” People were always trying to gauge how proficient you are in a specific thing.

And here you are, in the gray space. The bridge. While you don’t fit on either side, you are uniquely suited to connect them. It is its own superpower.

Right, it took me a while to see it, you know? Even when I started thinking about launching my own company, it hit me—I actually thrived during those early, fluid years at Facebook. And I believe it's because of my adaptability, something I think ties back to my immigrant background. You learn to adjust, to blend into various groups out of necessity. That adaptability, being comfortable with change and new environments, it’s been a huge part of my journey, and I notice it when I reflect on what parts of my career I’ve enjoyed the most.

You’re a translator.

Yes. Looking back, I realized “oh, that was a great strength of mine,” though I didn’t see it that way at the time. Back then, I felt like I didn’t truly fit in anywhere. I was just searching for something I could be good at, longing to feel a sense of belonging within a group.

Yeah. There's a loneliness.

Yeah. And a lot of fear. It's like when you reflect on your early 20s, everything seems more intense, right? I was constantly scared but at the same time, everything felt experimental. There was this innocence, not knowing what you don’t know. I remember having to write JavaScript for a feature without ever having done it before, thinking, “Okay, let’s give this a shot.” Despite feeling like I might not be good enough, there was this sense that it was okay to try.

But I was also dealing with a lot of insecurities, partly because of the young, intense, competitive culture there. Everyone liked each other, but there was also a lot of poking fun, taking shots, judging each other’s work. Facebook, in those days, was filled with very opinionated people. And that was tough for me because I wasn’t very opinionated myself. I was more of an observer, trying to understand and fit in, hoping to be accepted by the group. I worried so much about what folks said about me when I wasn’t around.

I really relate to a lot of what you're saying. Being the kid of an immigrant in the rural South, I was surrounded by people who were so certain about everything. They had this attitude of, “this is how things are, and this is how the world works.” But coming from a background with a parent from somewhere else, there was always this part of me that thought, "I know someone who would disagree with that." It often left me feeling confused, lost, and wondering what I was supposed to believe about anything. It's a lonely feeling, but in hindsight, I think it was a blessing.

I think it’s good practice to be more of an observer in a world where everyone seems compelled to posture and assert themselves. You can find it in the rural South and you can find it at startups. It's a universal fallacy. And it really makes me value the role and perspective of “outsiders.”

I find myself often connecting with “outsider” types, and I'm not sure if it's just coincidence or something more, but I tend to connect with them deeply. What we often have in common is having an immigrant parent—being raised in dual cultures from a young age. This upbringing instills a sort of void where concrete truths should be, but as you mature, you come to understand that “truth” varies widely from person to person.

Yeah, exactly. It actually took me many more years to come to that realization. Back then, people often said to me, “Wow, you made such a great decision going to Facebook.” But honestly, I didn't really know what I was doing. My decision was pretty much based on the fact that my good friend Wayne was there, along with a few other acquaintances, and I knew I wanted to be part of a startup. Facebook just happened to fit that bill. It wasn't some grand strategy; it felt more like following where the current was taking me.

And touching on what you mentioned earlier about seeking something... I realize now that part of me was subconsciously rebelling against my parents' expectations, while also absorbing their lessons about valuing stability. So, when choosing between a tiny nine-person startup and 100-employee Facebook—a product I was already familiar with and seemed to be on an upward trajectory—it felt like a no-brainer. Facebook was recognizable, used by people I knew, and cooler than opting for a lesser-known startup. It was this blend of rebellion and adherence to the lessons of seeking something stable and promising.

So, I ended up at Facebook, like I mentioned before, bouncing between sitting with engineers and designers, dabbling in frontend engineering and design, trying to pick it up as I went along. Looking back, I often think, why didn’t I just openly admire my peers’ work and ask for help? Like, “Wow, what you’re doing is amazing. Could you teach me? I’ve never learned this before. What exactly does this involve?” But I didn’t. Instead, I was trying to act as if I knew everything already. Reflecting on it now, I see that one of my biggest regrets is not being honest about what I didn’t know. At that time, I lacked the confidence to admit my gaps in knowledge.

Well, what's so interesting to me is… I can sense in you there's still this feeling of, “but I'm still not a specialist.” And there is some pain there. How long were you at Facebook?

14 years.

14 years. So what I've come to learn in my own grappling with my own non-conventional path, it's like… life is an endurance game, right? It's not a specialization game. Over time, that becomes clear.

Growing with a startup, especially to the degree that you did at Facebook, it's incredibly painful because, again, even if the startup doesn't die, the amount of change it has to go through is astronomical. Like, you saw 100 different Facebooks in your lifetime. You managed to survive because of your adaptability.

And for someone who's a specialist, or for someone who thinks that they know how things are done, that gets destroyed over and over. And that is painful. Like, a lot of people leave growth stage startups or end up hitting roadblocks in their career because they can’t handle that.

And so to me, you have a superpower that few people have. To survive that much time at a company that's undergone that much change. It's very different than 14 years at Microsoft. And I'm guessing it trained you in many ways for being a founder.

I can see that now. You know, I hadn't really made a lot of these connections. Up until this conversation, I hadn’t fully realized why I never deeply questioned changes or felt saddened by them. Stability wasn’t something I grew up with, so change always seemed natural to me. I’ve always looked for the positive or necessary aspects of change, perhaps because that’s the narrative I’ve comforted myself with. I don’t usually dwell on the past—my focus is more on the present and what’s ahead. I am a huge optimist. So when Facebook went through all of that change, I wasn’t thrown off. It never felt like a loss to me. I think I saw it as an opportunity to move forward, thinking the past wasn’t perfect anyway. We’re all just figuring things out as we go, right? But yeah, looking back, I realize a lot of my adaptability wasn’t so much a conscious choice as it was me just rolling with the punches.

"Stability wasn’t something I grew up with, so change always seemed natural to me. I’ve always looked for the positive or necessary aspects of change, perhaps because that’s the narrative I’ve comforted myself with. I don’t usually dwell on the past—my focus is more on the present and what’s ahead. I am a huge optimist. So when Facebook went through all of that change, I wasn’t thrown off. It never felt like a loss to me. I think I saw it as an opportunity to move forward, thinking the past wasn’t perfect anyway."

There were definitely times when I was like,” I don't know if I can do this. Like, I don't know if this career in tech will work out for me. I might need to start looking for a plan B.” There was a period where I was writing novels on the side–one novel a year for 4 years straight–and I think the reason I was doing that was because of this sense of, I'm not that great of a designer. I'm not that great of an engineer—this could end at any point. I might need to find another profession. So funny when I think about it. But those were the learnings– every single agent I queried rejected my novels, so as these experiments played out over time, it turns out I am better suited to a career in design than in novel writing or engineering.

So yeah, the trend of my life is that my subconscious was always looking for something that would be more natural to me. Because it never felt natural. Looking back, the story feels much tidier–it looks like a natural progression of growth and achievement. But it was really years and years of being afraid.

But I also think that that fear of failure made me really stubborn in some ways. I tell myself—I simply cannot fail. And so that did probably motivate me in a lot of ways to be more adaptive, to work hard, and to not call it quits.

I know so many people look up to you in this industry. And I am surprised to hear you say all of this. And I am finding myself glad to be talking to someone with all of the same fears and insecurities as me and everyone else.

I have no doubt that you were actually doing quite well, because you doubted yourself the most, and therefore did everything you could to learn everything about everything. I mean, you literally wrote a book about management, and this makes so much sense to me now—your desire to write a book. Anyone who writes knows that the process of writing a book involves learning everything.

Yes. That's why I was attracted to the idea of writing a book. Part of it was like, you know, it’ll look nice on the resume to write a book. But the other part was like, “Oh my God, if I write a book, I'm going to be thinking about these topics all day long. It's probably gonna make me better at this job.” That was actually a huge, huge part of why I decided to do it.

I feel like we're hitting on something kind of profound—the process of becoming a teacher in any way, in any context, is not preceded by you knowing everything. It's actually preceded by the desire to learn everything. Like… people write books because they want to figure something out. People create projects, people create art. People create literally to figure something out. It's not to share an answer. I think it’s to find an answer.

Right. And I know the feeling. Because honestly, if I have to write or put something into words that I already know well—it really takes me a lot of motivation to muster up the energy to do that. I’ll do it in contexts where it is helpful to others, but I want to operate and explore and write at the level where it feels like it's just at the edge of like… I'm figuring it out. That is where I find writing very fun and engaging. I can be in the flow.

Yeah, that I relate. It's part of why I'm drawn to do this project and the way that I'm doing it—like, I don't want to hear what I know. I genuinely want to learn from these conversations. And magically, that happens.

I think that's beautiful. Like, why not operate there? And this is also why sometimes I look back into my book. I'm really glad I wrote it then, because to be honest, I don't think I would write it now. I could not write the same book now, and I think it actually may appeal to a lot less people. I remember realizing I wanted to write it then, both because I was figuring it out, but also because it was very fresh, the idea of being a manager in tech. And the freshness made me feel like I could write a book for a first time manager that was better than what I could write ten or twenty years later. Again, if I were to write a management book now, it would be very different.

So with the book that you wrote in the past for a different time in your life. Do you feel like anything that you learned then has been instrumental for this phase in your life and career?

Writing about certain things was particularly challenging for me, mainly because my process often involves understanding the theory long before I'm able to apply it in practice. There's always this gap where I know theoretically what should be done, but I haven't mastered executing it effectively myself. So writing the book felt quite aspirational. I found myself thinking, “Wow, I'm putting these ideas out there, but I'm not fully living by them yet.” That realization was hard for me. The thought of someone reading my book, especially someone I manage, and noticing the disconnect between what I preach and what I practice was kind of mortifying. It actually became a sort of motivation—to start embodying these principles more earnestly. The fear of being viewed as a hypocrite, of not walking the talk, was a motivator to align my actions more closely with my words.

It's like humility has to be such a huge piece of the process, both in the desire to learn knowledge, but knowing that you’re going to learn all of the places where you’re off the mark.

Through writing the book, I discovered something really important: the theories I knew had to be lived, not just understood. It wasn't until I was deep in writing that I realized I needed to embody these principles more. Sharing these stories wasn't just about telling them—it was about processing and living through them myself. A big realization for me was a relatively simple one: you need to genuinely care about your people to be a great manager. There is no way to fake the caring.

"A big realization for me was a relatively simple one: you need to genuinely care about your people to be a great manager. There is no way to fake the caring."

It’s not that managers who focus purely on outcomes and efficiency can't be successful. It's just that, for the type of manager I aspired to be—the one I was writing about in my book—I recognized a gap between my values and my actions. Despite valuing the human element, I hadn't been practicing it as naturally as I wanted. I remember an interaction with one of my reports, Robyn, an incredibly insightful person who once pointed out that he felt I prioritized projects over people when I was under pressure.

That feedback led to a lot of soul-searching. It's a lesson I continue to reflect on, understanding that my fear of failing to deliver on deliverables and worrying about my own performance in the eyes of my superiors were hindering my ability to connect more deeply with my team. These are all things I still think about and work on.

Did making the leap to becoming a founder, carrying these doubts of “What am I doing? What am I actually creating?” force you to face these questions in a new or deeper way? When you started your company, did you have to confront this notion of value and creation more directly?

About a decade ago, I encountered the concept of “growth” versus “fixed” mindset from the book by Carol Dweck, which was a complete revelation at the time. Reading about it provided a framework that deeply resonated with me, even though it took a while to fully internalize. I used it like a new North Star; instead of the fear of constant judgment and the pressure I put on myself, embracing a growth mindset allowed me to accept where I was and believe in the possibility of change and improvement.

Growth mindset became a foundational principle for me, gradually shifting into my default way of thinking and significantly influencing my sense of stability and self-confidence. This transition wasn't overnight—it was a process that required time to understand and even more time to change my behavior accordingly. It was this journey that ultimately helped me make that leap into being a founder.

Did you find that process for you—would you say it was more time or more deliberate practice? Or both.

It's a bit of both, really. I hold this belief that time nudges us towards our intentions. So, if there's something I aspire to become or achieve, I feel like, subconsciously, I begin to drift in that direction. But this mindset also serves as a kind of solace for me, especially when I mess up. It's like, “Okay, I might have screwed this up, but remember, adopting a growth mindset means it's alright. Don't be too hard on yourself. You've learned something from this, right? We've gained a new understanding.” So, in a way, it's this internal pep talk I give myself, leveraging my analytical side to narrate a more constructive story. Once I started telling myself this narrative, it really helped temper the distress I felt over failures and setbacks, allowing me to view them as learning opportunities instead.

Can you tell me more about the process of starting your own company?

I think my decision to start a company was more about wanting to work with my friend Chandra than about launching a startup per se. We didn't have a clear idea of what we wanted to create—it was more like, “Let's work together and see what happens.” In the beginning, we ended up consulting because that's the path of least resistance when you're unsure of your direction. This phase was driven by my curiosity about how other companies operated, given that my entire career up until that point had been at Facebook.

We didn’t have a grand plan from the outset—it was more like, “Hey, automating some of our analytics work could be really valuable. Let's try building something.” So, it started as a small project, not as a formal “Let's build a company” decision. We thought it made sense to bring in a couple of contractors to see where this idea could go.

A few months in, what we were working on began to actually come together—it actually seemed like a viable product. Six months down the line, we took a significant step by incorporating Sundial and transitioning our contractors to full-time roles, and reducing our consulting work.

The first year felt like a honeymoon period. I was genuinely excited about our project. I wanted to see if the strategies we celebrated at Facebook actually led to its success, and if that could be repeatable in this scenario with our customers. This curiosity about the practical application of what I'd learned—whether it could withstand the "ultimate test" of starting from scratch—was a driving force for me. The first year was awesome—I was finally putting theory into practice, building a team, seeking funding, and applying all those lessons from Y Combinator videos I'd absorbed over the years. We had a lot of fun building and exploring.

Then came year two, and it was a wake-up call. Suddenly, I found myself questioning everything: “Who are we selling this to? What exactly is our product? What is our core value proposition? Why is everything taking so long to build?” We were receiving a ton of feedback from different clients, which ballooned into thousands of feature ideas, and none of it seemed to align. I began to doubt the quality of our product and its ability to be a painkiller versus a vitamin for customers. I recognized our product didn't meet the “painkiller” standards, and I was at a loss on how to improve it.

"Then came year two, and it was a wake-up call. Suddenly, I found myself questioning everything: 'Who are we selling this to? What exactly is our product? What is our core value proposition? Why is everything taking so long to build?'”

That year was challenging. So much doubt and frustration. I’d read about how this happens—how you enter the startup world kind of naive, thinking it'll be smooth sailing, then you get hit with “low lows.” Despite knowing that, living through it was a different story. The first year had been all about the highs. But as the second year unfolded, the questions and uncertainties piled up. I realized the extent of my own naivety and overconfidence. It was a period of introspection, realizing that I didn't have all the answers, which was both sobering and humbling.

Yeah, yeah. And then you question your entire life.

Yeah, and then the questioning begins. At that time, I wasn't fully aware of how deeply these professional challenges would affect other areas of my life. I had thought I could compartmentalize these aspects, but I realized that’s not really possible. I also noticed I had been crafting narratives for myself, narratives that I would then share with friends, not out of dishonesty but because I hadn’t truly allowed myself to deeply feel and process those experiences.

Absolutely. In all founders’ defense, we can't process everything—we’re just trying to keep it together most of the time. To fully acknowledge and feel all of the fear and stress seems almost impossible, given how intense it already is and how much we have to put into the work. Honestly, I'm not convinced we, as humans, have the capacity to process all of it simultaneously. I've tried, believe me, and what I've realized is that you can't rush these processes. I initially approached healing and self-discovery with the mindset of a startup timeline, expecting quick results, but it just doesn't work that way.

Yes.

It's very frustrating. But I think the body would literally just die if you had to process all of the stress of building a company at once. In the last couple of years, I started getting into somatics and body work and feeling emotions in the body and, and you begin to learn that the body can literally only handle so much. It is going to keep certain things from you until you have the capacity to handle it. And it sucks. It's frustrating, if you’re a startup-type person who just wants it all to be done as quickly as possible.

Looking back now, I realize how hard that was. At the time, I doubt I could've even admitted that to myself, let alone anyone else. I'd like to think that I've learned from that experience and that, in the future, I'll be better at recognizing when I need help. But back then, reaching out for help wasn't something I knew how to do. I pretty much handled it all by myself, and in a way, that solitude pushed me towards taking action. I've found that when I'm feeling lost or unsure, the one thing I do know is that I need to do something, anything. This was especially true during my postpartum days, where any action, regardless of whether it was the “right” one, seemed to help me break out of my funk.

"I've found that when I'm feeling lost or unsure, the one thing I do know is that I need to do something, anything."

So, in that challenging time, my mantra became “just try stuff.” It didn't matter if it was perfect or right; I needed to feel like I had some control, some choice in the matter. This led me to asking more and more dumb questions. I asked them of the engineers on our team, of any product or data leader who would sit down with me for coffee, of my co-founder and head of data, of existing clients.

It was surprisingly productive. It hit me later, this sort of obvious realization I couldn't grasp before: when I'm hitting a wall with a creative project, it often boils down to not understanding the users or the context well enough. So, diving into more user research and gaining that understanding naturally leads to better ideas flowing. That's exactly what happened. I recognized our product hadn’t nailed the value proposition, and I was at a loss on how to elevate it. But by engaging in more user interviews and deepening my understanding of the context, I found solid ground again. Coming from a design background, there's truly nothing that reorients and grounds me more when I'm feeling lost than listening to customers talk. It reminds me that at the heart of design is solving people's problems. Getting so intimately familiar with the users that you can almost predict their thoughts is when the ideas really start to flow.

"Getting so intimately familiar with the users that you can almost predict their thoughts is when the ideas really start to flow."

I feel the parallels to your early Facebook days of… just learn everything—learn everything about everything. And there's some obvious value in that, but there's probably also comfort in that.

Yeah, there definitely is something to it. When I deep-dived into listening, the ideas just started flowing. It was like suddenly, I could see clearer paths to taking action. For months, the most effective use of my time was having lunch with Stanley and Prasad, our head of engineering and head of data, and baragging them with endless questions: “How do you think about this? What's your take on that?” That persistence paid off, especially when combined with reaching out to prospective customers. It was like piecing together a puzzle.

And here’s the kicker—I was diving into building a data startup without a deep background in data. I mean, I shouldn’t sell myself short; I knew the problem we were tackling mattered a great deal. Having been at a data-disciplined company, I instinctively understood the value of making product decisions backed by data. I was familiar with A/B testing and metrics, but I hadn’t been hands-on with the data myself. The origins of data, the "plumbing" behind the dashboards and tools we used, those were a mystery to me. And I needed to understand them deeply to know how to build a good product.

Yeah.

And so, navigating my understanding of data was an enormous undertaking. It's a complicated domain. The first time I tried to outline all the different data tools available, I was overwhelmed. There were hundreds of companies, each offering something that seemed slightly different yet related, and I couldn't figure out how to make sense of it all. I didn't have a clear map of the landscape, and developing one was a slow process. I had many moments of thinking, “Ah, now I get it,” only to realize a month later that my previous understanding was still not deep enough. It felt like landing on an unknown island, not knowing its size or if I'd explored all there was to see.

The journey was filled with “unknown unknowns.” But gradually, through persistent learning and discussions, the map of this domain started to become clearer. While I recognized there would always be unknowns on this island, their scale seemed to diminish over time.

I'm reminded of parenting, how just when you think you've got everything figured out about managing a two-year-old, they turn three. It's like, you can master something to a certain extent, but then the world shifts or something changes.

I recently came upon the phrase “leave no stone unturned.” Like, really dig in and get to know the path you’re on. Don’t just race to the end of it. You might find out it’s the wrong path anyway, and you would have known if you’d really examined the path earlier. It’s a helpful practice, whether you ultimately take the path or not.

For you, it seems like there's this drive for knowledge that's key to your own satisfaction and has, evidently, served you well in numerous ways.

Yeah, definitely. Something that really helps me, and I think about this a lot, is how some people are just naturally uneasy with not knowing how things will turn out. But coming from a design background, I got used to the idea of trusting the process early on. In design, you rarely know what the final product will look like right at the start. But there’s this trust that if you keep trying things, gathering feedback, iterating, and then refining based on more feedback, eventually, you’ll land on something that's actually pretty good. I've seen this happen time and again, so I've come to rely heavily on the process itself, even when the end result isn't clear.

"Something that really helps me, and I think about this a lot, is how some people are just naturally uneasy with not knowing how things will turn out. But coming from a design background, I got used to the idea of trusting the process early on. In design, you rarely know what the final product will look like right at the start."

This way of thinking has been a huge comfort, especially when I find myself wondering about the future of the company—what it will become, how things will turn out. I don't linger on it because I have faith in the process. Most days, not knowing the exact outcome isn't something that worries me. There's no point in overthinking it. Focusing on whether we're taking the right steps in building the company day by day gives me a lot of peace.

Can you tell me a bit about the culture at your company and how you developed it?

I feel like I’m at a company where I'm really happy to be a part of the team, and everyone else there feels the same way. That's always been what matters to me the most – the deep relationships we build that allows us to do great work together.

Recently, I found myself in India, and the trip concluded with us pulling an all-nighter to celebrate a recent milestone. Here’s the backstory: In the past, my co-founder and I intentionally staggered our visits to ensure continuous leadership presence for our team, a strategy born from our desire to always have one of us accessible. It's a bit of a shame, really, since we used to spend a lot of time together, especially before COVID hit and while we were deep in our consulting work. Then he moved to the East Coast for family reasons, drastically cutting down our face-to-face interactions to maybe once a year, despite our frequent trips to India.

However, with his kids recently leaving the nest, he’s found himself with more freedom to travel, leading to more extended stays in India. By a twist of fate, his trip back to the US was scheduled right during my visit—a trip that’s hard for me to shift around due to my own family commitments. It seemed we were set to miss each other again. But then he came up with a plan: he'd be landing back in India at midnight on Friday, and his next flight wasn't until Saturday morning. "Why not have an overnight party?" he suggested. And so, we did.

Oh boy.

Yeah, I was totally into his idea. I mean, it's been ages since I've pulled an all-nighter. I'm usually out by 9:30 or 10. But, we thought, why not? It’s not every day we get to celebrate together, and we had just landed a major client, which was huge for us and definitely worth celebrating.

So, we decided to throw this big party, renting out an Airbnb for our team. Just to give you an idea, our team's pretty young, mostly folks in their early twenties to thirties, except for a few of us in leadership. We're the oldies with kids. Everyone else is in this vibrant, youthful phase of life, always ready for a good time. We had a blast. The Airbnb had a pool, and I knew from past experience that when your company party has a pool and the average age is below 30–everyone present would eventually end up dunked into the pool.

And then, deep into the night at around 3 or 4am, Chandra decides it's speech time. He gets every single person to stand in front of the group and share a piece of their heart, and it was just beautiful. It was easy to see how much we all cherished our team and its camaraderie. Hearing that was everything to me—it was just the best feeling.

So yeah, these moments, these connections, whether it's with our customers or our internal team, they ground me. They remind me we're doing something worthwhile.

I feel like there's going to be so many people reading this, like… “How do you do that? How do you build that culture? What is it? Is it specific mechanisms? Is it the intention?" Like, what are the foundational decisions that you have to make to create a company where people feel safe and loved, where they love their colleagues and are generating beautiful things out of that?

Absolutely, I've touched on this in the management book I wrote, and I think it's worth highlighting some experiences from our own company as well. Going through the process of starting up or leading any sizable creative project often becomes a journey of self-discovery. You end up learning quite a bit about yourself, and not all of it is pleasant. Sometimes, you come across revelations that are either embarrassing or make you think, 'Wow, did I really just do that?'

I'm a staunch believer in the idea that much of managing, building a team, or just interacting with others—since we're essentially dealing with interpersonal relationships here—necessitates that I engage in some serious self-reflection and personal development. It resonates with what you're saying: a company, or indeed any project, acts as a reflection of oneself and one's values. I've found that whenever I get caught in a negative thought loop, my team is quick to point it out. This feedback loop has been crucial, as it often highlights things about myself I wasn't even aware of.

"I'm a staunch believer in the idea that much of managing, building a team, or just interacting with others—since we're essentially dealing with interpersonal relationships here—necessitates that I engage in some serious self-reflection and personal development."

Let me share some specific examples. In our first year, as we built the team, I prided myself on my hiring skills, given my extensive experience. However, Chandra and I realized we were approaching hiring with a big company mindset, which didn't quite fit a startup’s needs. Despite hiring a significant number of people, we found ourselves questioning why progress felt slow and identified that much of our team, ourselves included, was operating with a big company mentality. This realization was a pivotal moment for us to reflect and adapt our approach.

Following that year, we received another important piece of feedback: our big-company management style was resulting in us being too hands-off. Coming from managing larger, more experienced teams, we were used to team members who preferred less direct oversight. But our team started telling us that we weren’t in enough of the details, especially for a pre-product market fit company. The realization hit us that as founders, we needed to be deeply involved and understand our business inside and out—no one else was going to do that for us. This was a tough pill to swallow, but it prompted us to adjust our approach and really get our hands dirty with the work.

So, after navigating through that adjustment for about a year, the pendulum swung again. I started hearing from the team, “Julie, you’re smothering us. You’re not showing enough trust. You feel like you know all the details, but you don’t; you need to let us make the calls we are better equipped to make.” That feedback was tough to hear as well. But these reflections acted like a mirror, showing me aspects of myself I wasn’t aware of.

I began to realize that when I’m under stress, I do one of two things – either disassociate, or try to control. Recognizing these stress patterns was a breakthrough. It explained so many past periods where I wasn’t operating at my best. I’m so grateful to our team for helping me realize these things about myself.

Now, that I see it more clearly, it’s easier to interrupt the pattern. When I catch that urge to control everything because I'm feeling uncertain, I remind myself there’s a healthier way to deal with it: by asking more questions. I express my concerns, sure, but then I step back and really listen to what the team has to say. What’s fascinating is how the data reflects that we’re constantly evolving. The feedback—whether it’s calling for more involvement or less—varies over time, mirroring our learning curve. Initially, yes, we were too detached. Then we swung too far the other way, but eventually, we found that balance where we could empower the team and truly develop leaders. This process isn’t linear; it’s full of adjustments, a continuous cycle of receiving feedback and recalibrating. It’s messy, but it’s also how growth happens.

"When I catch that urge to control everything because I'm feeling uncertain, I remind myself there’s a healthier way to deal with it: by asking more questions."

That answer will be extremely comforting to a lot of people. You learned everything you learned—you literally wrote a book on it—and then it's still hard. It's hard for everyone.

Yeah, navigating this was a journey in itself, especially since Chandra and I brought our experiences from Facebook, valuing that culture of transparency, empowerment from the ground up, and the whole ethos of speaking your truth. We cherished these principles, like holding strong opinions loosely and encouraging dissent regardless of hierarchy. We preached these ideals fervently, but embedding them into our team's DNA? That took time. Much longer than we anticipated, honestly. It seems the concept of truly feeling safe to voice different opinions wasn't something our team was instantly ready for, given it wasn’t what they were accustomed to.

Putting these values into practice, shifting from theory to behavior, was a gradual process. Now, we're finally seeing the fruits of that labor, with team members openly voicing disagreements and concerns, which is thrilling. It’s what we’ve been striving for. But, it’s taken us three years to reach this point where such openness is becoming more natural, and yet, I feel we still have a ways to go in deepening this culture. It’s a testament to the fact that fostering this kind of environment is a continuous journey, not a destination.

Yeah. It's making me think of this podcast that I just listened to, where Glennon Doyle interviews Dr. Becky Kennedy. Dr. Becky was saying that of all of the things she's talked about in her career, the one most effective mechanism to maintain healthy relationships is simply “repair.” Basically, every interpersonal relationship has challenges. And you should look at them as "opportunities for repair." This is the trick to longevity. And it’s not only to fix the inevitable tear, but it's the actual act of repair is this positive moment of bonding that is net positive. It’s just brings me back to how there are unlimited parallels between “work stuff” and “life stuff.” The solutions are usually the same.

Yeah, it really hits home for me, drawing this sort of dotted line between personal and professional life, especially when reflecting on the intense early years, particularly year two, which was incredibly challenging. I found myself caught in this mindset that because things at the startup were tough, I needed to pour all my time and focus into work. This, of course, led to significant conversations at home, with my husband pointing out the need for me to be more present and involved with the kids and family life, highlighting how I was leaving him to juggle the children's schedules and everything else.

We've had to navigate quite a bit in that area, but an interesting point he made was that perhaps parenting would be easier if I weren't so consumed by the startup. I disagreed, though. I believe that the startup journey, with all its demands and challenges, actually forces me to evolve and learn new things about myself, improvements that I bring into all my relationships, including parenting. It's like this whole experience compels me to grow in ways I might not have without it.

"I believe that the startup journey, with all its demands and challenges, actually forces me to evolve and learn new things about myself, improvements that I bring into all my relationships, including parenting. It's like this whole experience compels me to grow in ways I might not have without it."

I think you have to give yourself a break for not being fully there for everyone in your life during the actual entrepreneurship process. It’s just impossible, you are being stretched to your limit. So there are interpersonal costs, but I think the learnings ultimately make you a better person.

I can thank my entrepreneurial journey for so much, but I can thank it the most for forcing me to learn who I am. And it's a painful process, learning who you are. And I can say without a doubt that I am a better parent, friend and person because I was an entrepreneur.

I've come to realize that stress affects not just how I operate at work but also how I interact with my children. When I'm under pressure, I find myself again either trivializing their feelings–a form of disassociation–or nagging them too much–a form of control. Now that I've become aware of this pattern, I'm somewhat horrified to acknowledge that I've been doing this for years without realizing it. But, recognizing this behavior is the first step, and thankfully, I'm more conscious of it now and working to change.

Well, this is a great example. Your kids are too young to give you this kind of feedback, but with entrepreneurship, if you're running the organization in a way where you're open to receiving it, you've got feedback coming at you from all angles that you can't ignore if it is coming from enough people. Right? Then you can apply it to all areas of your life. And that's such a gift.

Yeah.

What advice would you give to any readers out there who are contemplating leaving the corporate tech world to start something of their own?

It all circles back to understanding your motivations—the 'why' behind your actions. We've discussed how articulating this can be easier said than done, but the importance of it cannot be overstated. Your reasons underpin so much of what defines success for you, shaping the strategy for the life you aspire to lead. Continually asking yourself about the meaning and purpose behind your endeavors is crucial. What do you hope to achieve? What outcomes are you seeking?

This reflection is likely to reveal a complex web of motivations rather than a single, straightforward answer. However, gaining even a broad understanding of your priorities can be incredibly insightful. It’s not about reaching a point where one aspect doesn’t matter at all—reality is rarely so black and white. Rather, it’s about recognizing the balance that exists, like maybe it’s 60% one thing and 40% another. That awareness of where your priorities lie significantly influences how you shape and direct your company.

Consider the common perception that getting VC funding is universally beneficial. Actually, whether it's advantageous heavily depends on your goals. There's a wealth of narratives out there, like the approach taken by the Basecamp founders, who've been vocal about the possibility of building a successful business without external funding, outlining why that might even be preferable. These perspectives are invaluable because they challenge the mainstream narrative that VC funding is a must-do for all startups, a narrative driven by the glorification of massive valuations and ambitious moonshots. However, that path isn't necessarily right for everyone; there are always trade-offs to consider.

I often ponder the concept of freedom, especially in the context of making choices. True freedom involves making informed decisions, understanding the trade-offs you're facing. But perfect knowledge is impossible—there will always be unknowns, especially if you're venturing into uncharted territory. However, there's merit in doing your homework, seeking out diverse experiences from those who have taken VC funding and those who haven't, those who regret their choices and those who don't. Listening to these varied stories equips you to make a more deliberate decision.

To me, that's what freedom really means: making a choice with intention and feeling content with whatever the outcome because you know you made the best decision you could with the best information you had at the time.

100% Okay, last question. How can the community support you?

If anyone is intrigued by the prospect of a modern, user-friendly tool for analytics and data visualization, they should definitely reach out to me about my start-up Sundial! Our mission is to help everyone at a company – execs, product managers, engineers, designers, marketing and sale, not just data scientists – better use data to make better decisions.

As someone coming from design and engineering, I often felt overwhelmed and confused looking at hundreds of numbers and charts. But of course I wanted insights to make better product decisions. My goal is to build a powerful yet incredibly accessible tool to get insights into the hands of decision makers, and that’s what we’re doing with Sundial.

Those interested in my thoughts on management should check out my book, The Making of a Manager. Folks who want to engage in product and culture topics with me can subscribe to my newsletter The Looking Glass.

Readers, if you ever use Sundial, or read my writing, or listen to me talk – please help me out by sharing feedback on how I can improve! I consider feedback a gift and will cherish it.