On Thinking Different, Staying Curious, and Faking It Until You Make It

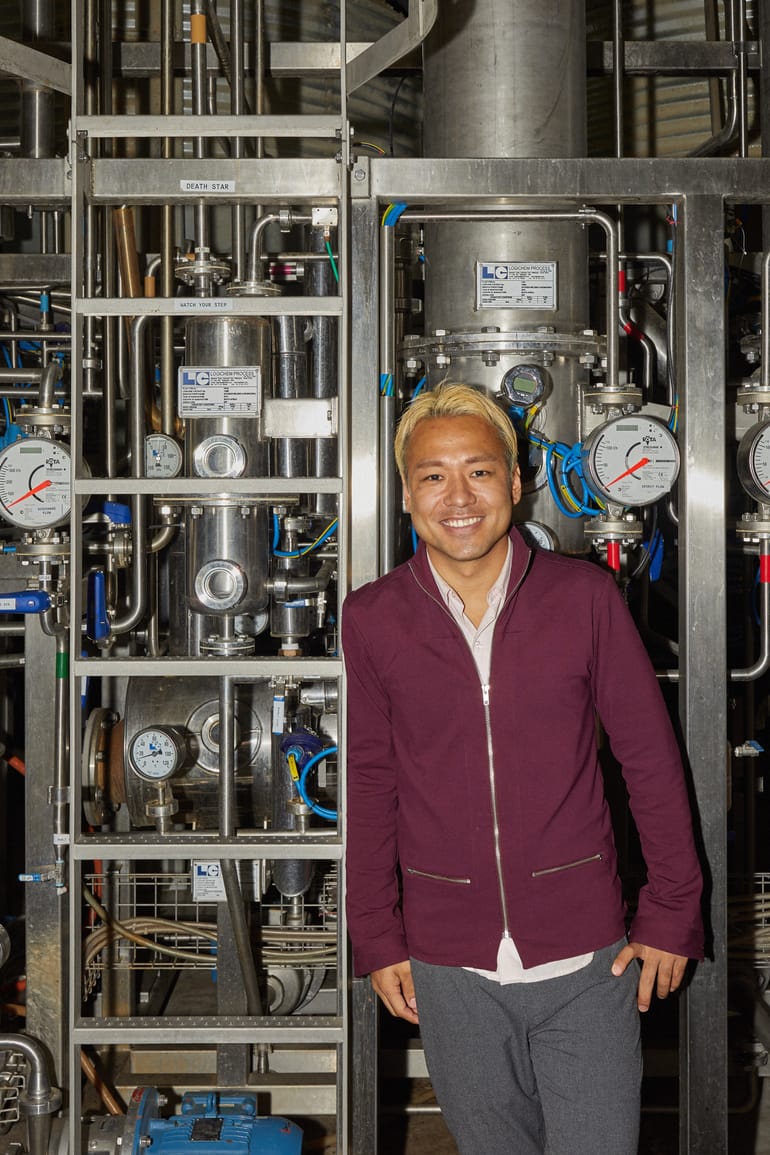

Emmett Shine is a creative entrepreneur from Southampton, Long Island. As the Co-Founder and Chief Creative Officer of Pattern Brands, he leads a family of brands focused on improving daily life.

Beyond Pattern Brands, Emmett is renowned for co-founding Gin Lane, an agency celebrated for its role in the success of major direct-to-consumer brands. Over its 12-year run, Gin Lane was instrumental in building over $10 billion worth of market share for its clients, including household names like Harry’s, Sweetgreen, Warby Parker, and SmileDirectClub. The agency's groundbreaking strategies in e-commerce and brand development dramatically influenced the consumer market as we know it today.

Growing up with a landscaper father and a painter mother, Emmett was shaped by a mix of hard work and creative exposure. Despite facing challenges in early life, Emmett developed a distinct worldview, using these differences to his advantage.

After working in landscaping post-high school, he eventually pursued photography in New York City, studying at NYU. Here, he honed skills in photo editing, design, and web development, setting the stage for what would eventually become Gin Lane.

Following Gin Lane's success, Emmett co-founded Pattern Brands, where he continues to blend creativity with his unconventional approach to entrepreneurship. Pattern Brands is actively growing its portfolio, buying and growing high-performing CPG brands.

Okay, so let us begin. Hello. Welcome.

What's up, Helena?

Thank you so much for joining. I'd really love to start at the beginning with you because I would consider your background nontraditional. And I love the story of how you hustled to where you are. So if you're willing, would you share some of that story with us?

Yeah. Thanks, Helena. Always great to talk with you. And I think this series you're putting together, it's so helpful and honest and special.

I'm from eastern Long Island. I grew up in the Hamptons. My dad's a landscaper. My mom's a painter. Pretty humble blue collar origins. They got divorced when I was in middle school. My sister and I had to really fend for ourselves for a while at a pretty young age. And, you know, necessity is the mother of innovation, or however the phrase goes. So we ended up with old school, hard-working ethics pretty young, because of our circumstances.

You know, we all have our our quirks. I'm neurodivergent. I was special education. I have Tourette syndrome, a lot of other learning disabilities. They made me think a little bit differently, and I was socially a little bit different. Luckily, everyone I grew up with was supportive of me being weird. And so I've always felt comfortable seeing the world a little bit different.

And my mom is a painter, so I grew up around people making art and thinking like artists. And it's not a hobby. It's hardcore—an entire culture and lifestyle. I've always gravitated to artists and creative types because that's where I feel most comfortable. And my dad's a really hard worker and he's creative his own way.

A lot of my motivations in the beginning were just to hustle so I wouldn’t have to be a landscaper for the rest of my life. Because that’s what I was doing after high school. I didn’t plan to go to college. But people eventually encouraged me to try and go. And so I just kind of was like, okay, I'll go to the city and try to make it as a photographer, and I just will beg, borrow, steal, do whatever I can to not have to go back home to the life that I had, which was just living with my mom, landscaping, riding my bike around town because I didn’t have a car.

I eventually got into NYU for photography. I didn't finish my time there. I found it really hard to focus because I was always trying to pay for everything. It was very expensive to pay for college on my own, to try to live in the city on my own. And I ended up dropping out because I was working so much that I just had to make a choice.

But while I was there, I tried to lean into art and commerce. I had learned computers at NYU. They had a digital darkroom. It was the early 2000’s. I taught myself the basics of photo editing and then design and then some basic web development. And I just started trying to sell my services to make money because I figured, you know, I could maybe make more money doing this than all the other pretty shitty jobs I was doing. At the time I was getting $10 an hour or $20 an hour working in retail or driving a forklift—you name it, I was probably doing it.

So that’s all the stuff I was doing. And after some time, it kind of started to work. And by my senior year when I made the decision to go into digital work full time, I was starting to make good money for someone who's pretty young.

I can pause there, but I think I have never really had a path. I've never really had a purpose. It's always just been like… survive and go to the next thing. I think now, almost 20 years later, I am trying to change my mentality to be more abundance mindset versus scarcity mindset. But for the first 30 years of my life, it was very much a hustler entrepreneur mentality, not because it was cool, but because I just had cortisol running through me. I just had to figure out how to move things forward.

Yeah, I relate to that. It actually makes me think of this podcast that I listened to a few months ago. It was Huberman interviewing Jocko, I think. I’m guessing you’re familiar with at least one of them.

The Andrew.

And about 20 minutes in, Jocko, a military guy, was putting folks from his world into two categories. One type is really good at simulated combat. To be good at this you learn the game, and you're good at politicking and sucking up to the right guy and speaking authoritatively. They do great at working their way up the ranks. But then when real combat comes, these guys do terribly. The ones who do well in combat are the other type. They're kind of creative types, the weirdos, the black sheep. They're really not into the simulations and the game. But once real combat comes, they excel.

I just happened to listen to that podcast the week that Silicon Valley Bank was collapsing. And I couldn’t help but notice the parallels between what he was talking about and what we were observing in Silicon Valley. The guys who seemed to know everything at peacetime were absolutely losing it when shit started hitting the fan. And I’d argue we’re still seeing that.

So when I hear about your upbringing, I can connect the dots that your situation made it hard for you to follow a conventional path, but it was the very thing that has allowed you to do what you do, and it makes me not worry about you one bit in wartime, now or in the future.

I think there's different strokes for different folks. I struggled in school settings. But I think in a professional setting, I've found an area where it works for my personality. Even my wacky Tourette's, where I can’t always control my thoughts and stuff—I have different ideas pretty spontaneously and I can connect disparate things in ways other people can’t. It is one reason why I always said the business we would build after Gin Lane would be called Pattern Brands. Because it was pattern recognition—we were always great at seeing lots of different things that other people may not see. I think, a lot of times, weaknesses can become strengths.

I had to go through some tough times, and I’ve done therapy and all that stuff. But I'm very self-sufficient, my sister's very self-sufficient, and I had to also use weird ways of thinking because I couldn't win in any of the traditional ways. I just couldn't get ahead of the curve. And I also think it gave me a lot of empathy, once I ended up doing well. I don't think I'm a typical kind of successful-guy-jerk. I love underdogs. I try to always be there for anyone that is taking a risk, taking a shot, who doesn't feel heard, doesn't feel seen. Those are people I love working with and mentoring.

And I think on the flip side, you have to be conscientious that your strengths can become your weaknesses. And so whatever you used to win the video game of high school or college or your first relationship—it may come back and nip you in the bud because you're still relying on those behaviors. But as you evolve in the chapters of your life, those ways of navigating your reality don't always apply forward.

“I love underdogs. I try to always be there for anyone that is taking a risk, taking a shot, who doesn't feel heard, doesn't feel seen. Those are people I love working with and mentoring.”

For sure. I want to go back to the beginnings of Gin Lane. It all started with the digital work you were doing as a side hustle in school. And when I met you, Gin Lane was king. You were at the top. You had helped build multiple billion-dollar brands at that point. It was just incredible. Everyone wanted to work with you.

You know, I've always been so heads down about my work that I tried not to get too in my head about it. Gin Lane generally came out of me freelancing from NYU. I was doing photography, I was doing web design and graphic design. I had design jobs at Rocawear and VitaminWater, I had a skateboarding company. I was making CDs for musicians. I was doing so much.

And whenever I would get a project as a freelancer, people just never would pay me. You know? I was in my early twenties, living in Chinatown, didn't really have connections or mentors or older people cosigning me. I was just kind of out there on my own. All my friends were skaters or, you know, worked in bars or nightlife. No one to really show me the ropes on how to work with clients.

And I’d get these jobs with Pepsi's creative agency, or Universal Records, where someone recommended me for the job. And I'm like, okay, I'll do the work. And they’re like, “Great, thanks—we'll pay you in six months.” And I'm just like, I can't do that. I have to pay rent. I need money, you know?

So I came with this idea that if I said I work for an agency, that people would take it more seriously. I had a friend who was pretty confident in a way that I wasn't about business. I was scared of money conversations and stuff. So that friend agreed to get on the phone and do the business conversations for me.

I'm from Southampton. There's a rich road there by the ocean called Gin Lane. So my little mind was like… “Oh, I'll call it this rich thing.” I made the font all serif-fancy, and it was all pretentious looking, just so people would think it's like a legitimate agency. I put an address of an office in Chinatown that was a friend's office, and that was that. You know, you fake it ‘til you make it.

One thing led to another, and after like two years of completely faking it, it actually went from just freelance work—hiding behind something where my friend would call people up and yell at them to give me money—to where we started to get requests for bigger projects because I and a few people I’d bring on were doing good work.

We used to do projects for pennies on the dollar in exchange for word of mouth. I’d do a website for $2,000 or something. I just asked that they refer me to anyone who has money.

One of these people was a photographer, Tim Barber, who's gone on to become quite esteemed. He had worked with Ryan McGinley, and then he got put up for a job for Stella McCartney. During that shoot, he and the client were talking by the monitor during a lunch break, and they said that they wanted to change their agency and needed a cool digital team, but they just couldn't find any cool digital teams in New York. He recommended us.

So Stella McCartney’s team came to our office—but we were still faking it, so we used someone else's office. We put a bunch of people in the office to look like we had employees. And we won the account. It was completely bullshit, made up. And Adidas, who was doing the work because it was Adidas by Stella McCartney, were so mad. But Stella had the creative control and they wanted to work with us. Adidas had to spend like a month onboarding and training us on how to work professionally because we were in our early twenties and had no idea how any of this stuff kind of worked. But we figured it out.

“We were still faking it, so we used someone else's office. We put a bunch of people in the office to look like we had employees. And we won the account.”

Anyway, we ended up working a lot in the fashion sector after that, which I liked because it's creative, it's weird personalities. You're on shoots, you know, people are giving you very ambiguous briefs. And we were using the medium of websites and apps and installations, which was very free for all, which I like because I don't like being told what to do. I like to figure things out. And so there wasn't a lot of definition in those days in terms of how to build, you know, motion into a website. And we were very, very experimental.

And that caught the eye of this whole new class of business operators in the early 2010’s. It was post-Zappos, where the guys from Bonobos, the guys from Everlane, the guys from Warby Parker, they all contacted us and said, “Hey, we see the stuff you guys are doing with websites for fashion brands. We'd love to take that type of thinking and apply it to what we're going to do.” That ended up becoming the first wave of digitally native, vertically integrated brands, which ended up becoming DTC.

Those guys were not as cool as, you know, Helmut Lang or Theory or Tom Ford, but they were really smart about business. And so me just again, being curious and with that survivor mentality, I'm just always trying to learn. I'm always trying to stay ahead of the curve. I really enjoyed hanging out with them and learning and working, and there was a lot we could kind of offer up as well.

I'd never heard of venture capital. I never heard of, you know, equity or a cap table or any of that stuff. The guys from Harry's—they were like, “Hey, we want you to launch this brand. We want you guys to do the website, all the art direction and photoshoots. You're great at it. But we only have this amount of money.” I said, “Okay, but that will cost a little bit more.” And they said, “We're going to give you some equity in it.” And I’m like, “I don't know what equity is, just give me cash.” And they were like, “Dude, we're actually hooking you up. Like, this is going to be pretty big. Just trust us. It's better than a few thousand dollars difference.” And they kind of all laughed at that and thought it was cute. And so they started to educate me on what equity was, and wealth creation and all that. And that was the beginning of a whole other chapter of learning for me. Josh Kushner and Kirsten Green and that whole cohort—I ended up spending a lot of time and just learning from them and everyone they were working with. It could be Emily Weiss, it could be Oscar, Sweetgreen—we just got introduced and we were there at the right place and right time.

But I never thought of myself as really great, or exclusive, or at the top. I was just trying to always go to the heart of the center of innovation and creativity. And that's always been what I try to focus on because I think that'll put you in a good place if you just focus on that.

Yeah, what a great story. Two words come up for me—curiosity and enthusiasm.

Those are great words.

Like, what are the qualities that can really give you the sauce as an entrepreneur, you know? Those are the ones I continue to come back to.

And it’s not like you can just snap a finger and have them—it might take some practice if it's not natural to you. But I think so much about what has driven me as well. And it's not confidence. It's like not any of that cliche stuff that people talk about. It's straight up curiosity and enthusiasm and they both tend to be kind of weird and wonderful qualities.

I think that those could be the words of the day. If you can combine curiosity and enthusiasm, you can go anywhere, you can do anything. They're way more powerful than confidence. You don't need to be confident.

You know, I think a lot of problems we struggle with are feeling that we should be confident. I kind of feel uncomfortable when I'm confident because that's when I make mistakes. I like feeling nervous and the pressure of not knowing what I'm doing. I think that was the double-edged sword of Gin Lane succeeding—we ended up becoming really good at something. And I think I felt a little uncomfortable because I wasn't sure where to go or what to do next as a challenge. And I don’t do well if I'm not really challenged.

Yeah, for sure. So in the beginning you were doing every kind of job that was handed to you, and that helped you get to where you are. At the point when you became very successful, did you find that you became more discerning and saying no to projects?

To answer this, I think back to mental disability stuff. I'm so close with my childhood friends and they've been like brothers to me and would protect me on the playground in elementary school. I’d be making weird Tourette noises, and the other kids would be like, “What is going on with this guy?” There would be lots of kids that were bigger than me. I didn't want to get beat up, so I needed to find ways to talk and get along. And so my childhood experiences made me really good with people, and ultimately with teams.

Like, I like individuality. I'm a skater, I'm a surfer. I like individual pursuits, but I also really love team sports and collaboration. I say all this because I never said no to anything. And what I learned was that I'm good at some stuff and I'm not good at other things. So in school, if we were to do a project and I couldn’t read or figure something out, I would develop really good soft skills of convincing people to work with me and work as a team. And later in life, I did that with Gin Lane.

I got partners at Gin Lane that I brought on—Nick and Suze—that had very different personalities than I did. They are very discerning, and conscientious of their time and effort. They were very protective of myself and Gin Lane, because anyone who would come into the door, still to this day, I'm like a little kid.

You know The Rock? Like, he is like such a famous guy that is so nice. Everyone will ask him for this or that, and he just says yes to everything. He has a team around him that just protects him because he will never get anywhere on time. He'll never save any money. You know, he has a whole professional group that he's organized because he's just him, and he can’t say no to anyone.

“I'm always doing too much because I think that's just my nature. I just don't fight it. I'm just crazy and manic. And I think it just makes me happy.”

So I'm not saying I'm The Rock, but I’m similar personality wise, like I still am doing too much. Like, I'm in L.A. right now and I'm like, Oh, maybe I'll try to make a film. And yesterday I'm with this guy who directed Spider-Man into the Spider-verse, won an Oscar, and he's starting a film studio. And I'm just sitting there last night, just helping him put together a new studio. And I'm, you know, it's 6:00 at night, I could be watching a TV show or just thinking about my own stuff, But I'm always doing too much because I think that's just my nature. I just don't fight it. I'm just crazy and manic. And I think it just makes me happy. And I have to just choose people around me that understand that. I'm recently married, and my wife—the one thing of many that I love about her as she understands boundaries way better than I do. She helps impose them on me and protect myself from what I'm bad at.

That’s really nice to have. I want a protection team. That sounds wonderful.

Was there a moment when you felt the energy change of, like, you hustling for everything to it all suddenly coming to you?

Yeah.

I’ve experienced both too, and I’m curious, of those two experiences is there one you prefer? I ask because being in demand can be stressful and relatively unproductive if you don’t have boundaries.

Yeah. I get a lot of people that are just normal humans that will message me on every single platform there is. And I try my best to write back to every single one because I remember when I was younger and I would write to, you know, a graphic designer or someone that had a cool photo studio or someone that worked at an agency, you know, and no one would ever get back to me.

I remember going to offices or just in New York City, just being like a broke loser that doesn't know anyone. And it was like two years of just feeling so alone because no one knows you and no one cares and no one writes back and no one answers anything or follows up. So I always remember what that's like and have a really soft spot, when people are real humans and they send you a cold outreach. That's how you and I met. And, you know, your story seemed really compelling. And then we built something together, which is awesome.

And then I have other friends, where they really struggle with their time because they are very successful and they have families now. When I’m reaching out to them, I’m trying to be respectful because I know both sides. I’m like, “Hey, do you have any time in the next month? Like literally five minutes. And here’s what I would want to talk about.” That’s a good practice for anyone to adopt. Just come with respect and understanding.

Do you ever feel guilt for how you wish you could help everyone but you just can’t? It's a silly question, but it's something I struggle with.

Yeah. What I've tried to do with that is to focus on acknowledgment. I may not always have the ability or answer to spend time with someone or answer something in depth. But I just picture it as if I was a kid and I was like yelling at a sports player walking by, they could just nod their head at me and I would feel so special. They wouldn't have to come over and have a conversation. Just a nod of acknowledgement.

You know, there are filters where there are some people that just are crass or they don't seem empathetic. But if anyone puts effort into reaching out and they seem like a normal human and it seems genuine, I always try to just acknowledge their presence because I know when you're really lonely or sad and you feel not acknowledged, it makes you feel invisible. And this goes for everything I do—at a coffee store holding a door for someone, or giving a guy a buck on the side of the road. It's not life changing. They're just acts of acknowledgment.

I love that. And I don't think that's a term I've ever heard. Not acts of kindness. Acts of acknowledgment.

Yeah, I think people just want to be seen as existing.

Okay. So I think there's something I'd like to demystify for people, which is this idea that when you're “successful,” when you're at the top of your game—once you reach that point of success, that life is good and your problems go away and all of your desires are fulfilled. Can you share some challenges that specifically came with success?

Yeah. I mean, you know, when Gin Lane got, perception-wise, very successful, it wasn't like I or anyone involved became rich. It’s a weird situation. You're building all these businesses that are doing so well and some people are making a lot of money. In that specific case, it wasn't like I was a big zillionaire or anything like that. We got equity that ended up down the road being great, but for those times and periods there was this perception that didn’t match reality.

And you know, it goes both ways. I think sometimes people think I'm doing less well than I am. And a lot of times people think I'm doing more well than I am. So again, I try to just keep my head down and focus on the work and stay busy, because once you get caught up in your thoughts is where you just get in trouble, period.

I've had very formative parts of my high school and post-high school days where I was hanging out with the wrong crowd, getting in trouble. You name it. Like, I definitely was like a lost cause for years and I ended up turning around and having great success with different groups of people who don't know that part of my life, and I don't need to impose that on them. But I know from those periods—I've seen a lot of people not get out of it—they just get stuck in their head, way too worried about what people think about them.

And so you can have a modicum of success or where people can look at you with adulation. And it is strange if you're not used to that and it can be an ego trip. And I think the best salve is you’ve got to just be humble. You’ve got to put your head down, you’ve got to focus on what matters, which is being a good person, being kind, caring for your family, caring for your friends.

And if you really are about that life of your work, be the best craftswoman or craftsman you can be. And that is enough to keep you pulling your hair out every single day because the work's never done. It's like Jiro Dreams of Sushi. He doesn't care if he's successful or not successful to the outside world. He just cares about himself. There's like a nerdy Drake rhyme where he's like, “You know, I do it for myself at this point because if I was doing it for you guys, I would have just quit a long time ago.” Like, I've already done everything you wanted me to do, but now I'm just my biggest competitor.

So you chose to close Gin Lane when it was at the top. And I feel very honored to be one of your last, if not your last client. And just as an outsider, to me, it just was such a testament to your unique way of thinking, because I would not say that anyone on the outside really understood why you would shut things down when you're on the top and go start something new. And I'd love to talk about what you were thinking at the time.

Yeah. You know, it was a pretty fascinating moment in my life and, I think, a lot of people's lives. Because it was strange. It did not seem like it made sense. I think people did look at it as like, wow, this is really cool. But also, this is befuddling. I think there's a lot of different ways to look at it that tell a lot of different stories.

And again, I've got two great partners, Nick and Suze. We ended up founding Pattern Brands together. And really they're, I would say in this incarnation, the leaders of Pattern Brands. And so I would say there's my perspective, but I think there's also different perspectives and I think some of the holographic ways to look at something from different angles.

From a business perspective—because the Harry’s guys gave us equity and taught us about that, I think I got obsessed with it. I was like, “Oh, wow, I don't want to just be paid as a contractor anymore.” If I'm doing something which is so valuable and I'm seeing all these businesses go from two guys coming into our office with an idea, to a few years later, you know, they've raised tens of millions of dollars, are doing sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, and the businesses are worth so much, like, how is that worth $50,000?

And because I got so obsessed with that, we ended up getting a lot of small equity in many businesses so we could see the financials and then see who is a great operator. And Nick, who was a Harvard Business School graduate and a strategic consultant, started looking at all the financials and saying, hey, there are some really world class people we're dealing with. But there's also a lot of folks that are presenting stuff where it just doesn't seem sustainable. It doesn't seem like the business models make sense. It doesn't seem like the economics will really play out. Maybe right now they do, but it just fundamentally doesn't seem sound.

And this was around 2017 and 2018. And at the same time, I never wanted to make Gin Lane big because there wasn't a huge market. I didn't want to do Nabisco, I didn't want to do Heineken. Back to your military person analogy—I don’t do well in corporate settings. I always argued with people. I always felt frustrated at the lack of speed. I loved startups. I loved working with founders directly, affecting the change, going right at it. And then there's a developer, there's a designer, the strategist. You spin something up right away, you test it like, that's my addiction. It’s that immediate kind of feedback loop.

“I loved startups. I loved working with founders directly, affecting the change, going right at it.”

And so we had this idea that maybe we could just try to put a bunch of business together that would be profitable and small. Our team was maturing and getting married and having kids. And people need more money and more freedom. And so we kind of found ourselves in this place where we were really good at what we were doing, but we started to feel like a big fish in a small pond. If you really took a step back and looked at it and we wanted to get out of that pond. And so we spent a year and a half trying to figure out what to do. Do we raise a fund and we invest and we incubate? But we didn’t know how to do any of that. What we do know how to launch businesses and we're great at it. And so that ended up being the decision we made, when we went out to go raise.

And, you know, even though we were so well regarded, no one gave us a dollar for a year. So we had to keep using overhead or get to keep using money from Gin Lane to define the incubation of Pattern Brands until finally an investor said, You know what, you guys are completely unqualified, you're probably going to be a disaster as operators. But we bet on platforms. We're going to do that, we're going to bet on this. And once they came on board, then a bunch of other investors came on board. And sure enough, you know, we transitioned from Gin Lane to Pattern Brands.

It was great. And then we had some real challenges at first—figuring out how to operate, how to manage supply chains. And, you know, we had muscles that were so different.

It's taken us four years, and a pandemic. We're buying businesses now, which is an evolution. There's so many things that have changed, even though the overall architectural goal, which is to have a portfolio that's more sustainable by having profitable businesses—it is working. We're building a growing, big portfolio.

But it has been hell or high water—really difficult, especially we're not spring chickens, you know? I just turned 40, so being really good at something and then jumping into something else. When you're totally a mature professional, it's doubly hard because you're used to being good and now you suck, you know? So it's a good challenge, but it's not easy.

Oh, man. It makes me think of… famous last words: “I can do what they're doing.” (laughs) I’ve been that person my whole life, and it kicks my ass every time.

Well that’s what they say about being an entrepreneur. The difference between being an entrepreneur and a normal person is that a normal person sees that they shouldn't do it.

Yeah. I mean, I've come to think of it as this funny gift, right? Like, like you said, I wouldn't have done any of the things that I've done if it weren't for this funny arrogance slash naivete of seeing something and being like, “Yeah, I can do that.” And then you get so humbled in the process that it balances out, I think.

Well, that's why I think this series is so great because it hopefully can be a support system too. Part of the bravery of your narrative of saying you take risks, you take swings—it doesn't always work out perfectly or how it is expected or how it should be. But it's the journey, it's not the destination. And you learn a lot about who you are and the process you go through. And if there's other folks that more gravitate to that, that's really inclusive and really powerful versus being a destination-based narrative.

I mean, your story's such a great example of that, right? It's like you reached what many people would think from the outside is a destination, right? Of being the best at something. But you had the foresight to recognize that markets change. You also wanted to continue learning and growing and doing more things with your life. And you saw the writing on the wall before most of our industry did. Right? And you just understand that you’ve got to keep moving.

Yeah, you’ve got to keep moving.

I think one of the most valuable mindsets I’ve had, which sounds like you also have—in whatever job I was in, I’d always ask myself, “How does this ladder up to the next thing?” Like, I was always thinking two jobs ahead, you know? And obviously you try to do your best job where you are, but you have to understand that that is only a stop on your journey. Because wherever you are—this isn't the end at all. It never is, you know.

Yeah, 100%. I think also like when I was younger, I didn't have any mentorship or support groups. I had my crew of friends, which was great, but maybe not professionally great. And I didn't also want advice from anyone. Classic young guy.

And I think now, for example—we banked with Silicon Valley Bank when that whole thing happened. We immediately sought out other entrepreneurs and investors that were going through that situation. And I think that was normal for us at that point. And a difference for me was being more comfortable with being a part of support groups, or having different people that you can kind of talk with that have empathy and can relate.

I think I always was scared to ever show weakness or vulnerability, but it isn't being weak. It's just life. And I think we are tribal social creatures. And again, back to this series you're doing, I think if people can be more inclined to create support groups and systems with other empathetic folks that are going through these experiences of trying to build businesses have a lot of pressure, like go home and be present to their family, have time for themselves, like it's really hard and you have to find ways to cope with it healthily or else it'll take a real toll on you personally.

“I think I always was scared to ever show weakness or vulnerability, but it isn't being weak. It's just life.”

Given your own habit of looking ahead and seeing patterns… What do you think the next wave of entrepreneurship is going to look like? What are your thoughts on the next gen of consumer brands? What is it going to be like for these new founders?

So we've got seven businesses at Pattern Brands. And if there's any folks that are listening that have awesome brands in the home goods space, come talk to us. We also have a pretty cool referral program. So if you know a brand that's out there, let us know as well.

All the businesses that we've bought have been based on EBITDA multiples because they've been profitable and almost none of them have really raised any outside capital. They've all, you know, really kind of nickel and dimed these multimillion dollar businesses. Some of them were Kickstarter launched, and they had to find product market fit, unit economics, gross margins and an economical way of growing their business from the early days, or else they wouldn't have the ability to move forward, you know? They had no choice.

So I think that's something that has been really powerful to see. And the big motivator for us at Pattern Brands and how we started to look at ourselves and how we were acting and operating. And I would say the one thing I've learned over the past two years of all this is like just trying to keep my cost basis professionally and personally as low as possible so that I can take more risks and I can try more things.

And I think if you can find ways where you have a little bit of freedom, it could be time, it could be money. You could take those risks. It's really hard, you know, if you're a single mom, you know, when you're young to find time to take risks or be creative, you know, it's why if someone is maybe in a little bit more of a stable situation, they can go take music lessons or do piano and, you know, end up excelling at something which is non-linear of a profession.

So I think, again, that's where support groups come in. I think it's about finding other people that are going through what you're going through, but for whatever whacky reason, have the desire to do something entrepreneurial or creative and to not feel bad if you don't have it all figured out.

What I've seen is many people in New York City that I was coming up with in the early twenties or my early twenties. You know, some of them are dead. Some of them moved back to where they're from, but a lot of others, they persevered and they are different degrees of success. Some are super successful, like literally international superstars that I knew when they were broke in New York City, like phenomenally famous, wealthy, successful superstars. And others are not that, but they're quietly successful. They're just excellent at what they do. Even when they were in their thirties, they still were struggling, but they just never gave up. They had the right attitude. They stuck with it and they created an environment where they could take multiple shots on goal. So you do a startup, you raise, you try something, it doesn't work out. Maybe you still know so much more than someone that's never been through it. And you're so much more bankable. You're so much more worthwhile to work with. You're in the ecosystem.

The nineties into the dotcom bubble of the early 2000s, the Great Recession of 2008, COVID. There's always crazy things every X amount of years that are going to happen. But if you're born in a recession or your business was in a recession and you could make it out, you know, you're that much stronger. So what I've seen for consumer businesses is just more autonomous, independent, economically sound businesses is the right foundation for you to then do the creative fun stuff. Otherwise it is just lipstick on a pig.

Totally. Okay. So I've known you for five years now. I’ve seen you go through a lot. How do you feel like the last few years of your entrepreneurial journey has changed you as a person?

Yeah. I mean. I kind of ended a whole chapter in my life, you know. I ended something that I ran for 12 years, the agency. I ended a long term relationship. I, for a while, moved out of New York State. I completely restarted my entire life and I think it's been immensely humbling.

At Pattern Brands, we're doing good. It's been really hard and a lot of work. And we've got a great team, great operators. I've got great partners, we have great investors. But like, it's been deeply humbling to not be great at something, to start to walk into a room and people don't think you're great at something when you know, maybe you were great at something else a month ago. I felt lost. But I think I wanted that. I think I wanted to restart everything. And I just didn't feel comfortable when everything felt good. I felt that I still had a lot of growth and learning to do as a person.

And I think that's truly what entrepreneurship is, outside of business. It's taking an idea and turning it into reality. On a personal level, I think it's marrying your business with a sense of discovery, a sense of exploration and a sense of evolution. If you're entrepreneurial professionally, it's going to personally drive you to continue to evolve. And I felt I had a lot more evolution to do, and I maybe felt uncomfortable where I was that it wasn't going to fuel the evolution that I needed long term for who I wanted to be as a person.

“If you're entrepreneurial professionally, it's going to personally drive you to continue to evolve.”

And I don't have the same success or whatever now that I did then, but I think a different level of success personally and I think professionally is coming. And I wanted to bet on myself, you know, for the future. But that meant feeling like a loser again for a few years. It's been hard. And I think it's important that people hear these narratives because from the outside looking in, I'm sure Pattern Brands looks great. But inside it's just like any other business with a lot of pressure and you don't know what you're doing and you're trying to figure it out.

It’s funny hearing you say you “don’t have the same success,” because in my opinion, your success never goes away. Those accomplishments will always stay with you. You still made what you made. It’s also funny because I do the same thing.

Yeah. I mean, we have chapters, you know. I would compare what we're saying to an actress or an actor, where maybe they're part of something spectacular early on and then their career goes in a different direction. Maybe they have some films that don't work or they go indie, but when they reemerge in their fifties or sixties, all of a sudden they do a character actor type role. But for a film that does really well, surprisingly, and then they go and they win an Oscar or something, right? Meryl Streep wasn't always Meryl Streep. She was Meryl Streep, but she also did a lot of weird movies in the eighties and nineties, too. But she's been working forever, you know? So I think in that lens it’s like… there’s a long road ahead and not everything you do will bring you fame and fortune. You’ve got to be pushing yourself, you’ve got to be challenging yourself and you’ve got to be doing it for yourself.

Yeah. It makes me think back to what we were talking about earlier— thinking two jobs ahead or whatever. The best thing we can do with moments of success is applying it back to the work, over and over again. It's not about clinging to that moment and needing this one thing to be successful forever. It’s about constantly thinking, how can we utilize these moments of success or these accolades or even the hardships, Right? Both moments are fleeting. We have to make use of them.

I think if we're lucky enough where we have agency—and not every one in every moment has that—we have an ability to think about what we want to do. And sometimes we make missteps or we make decisions we think are good that ultimately end up biting us in the butt or aren't great. But if you have that ability to have agency, I think it's so powerful to stop and realize that you can design a lot of your reality.

There's parts of it where you can't fight physics, you can't fight gravity. There are, you know, challenges and limitations economically, socially, like those are real. And I think it's important to acknowledge it. But I do think that you can design a lot of your reality and you can ask yourself, “What do I want to do?” And then just work with the voices in you that answer. Some of them say, “You can't do it, you don't deserve it. You shouldn't do that.” And others of them say, “Hey, let's go try that out. You can do it. This would be fun.” And it's about finding silence where you can listen to the voices. And if you can listen to the positive ones, that's really exciting.

And as you're saying, these are just chapters of your life. You know, like you've had some chapters that some people know more about and some chapters that people know less about, but they're all your chapters. And how can you look backwards on what you've learned, which is part of growth and experience and evolution and design a forward facing reality that is where you want to step into. In your case, what you’re doing can positively affect other people around you from the wisdom and learnings that you only gained through firsthand experience.

There’s an old interview I did many years ago, and the reporter interviewing me was talking about how she’s interviewed hundreds of founders and they all say the hardest thing is figuring out an authentic founder's story. Which was so funny to me, because you don’t create an authentic founder story. You already have it within you—it’s your own experiences and your own desires that make you uniquely suited to build a particular thing. I think the real challenge is getting in touch with those things and realizing that they are enough of a reason to build something.

I mean, you know what goes into making a successful brand. I know that we both align on the importance of authenticity. There are a lot of people out there looking to build a brand of their own one day, and they may not know how to really incorporate authenticity into the foundation of their brand, or whether it’s even appropriate. Can you share your thoughts on this?

Yeah. I mean, you want to have a defensible moat, and there's no better defensible moat than just who you are—no one else is you. And that could be for a startup or entrepreneurship or creativity or dating or anything. It's just really embracing who you are. And not just your physical manifestation—but also just how your brain thinks or how you represent yourself.

I think a fascinating and interesting and scary—but also amazing—part of digital is how we can create essentially new representations and avatars of ourselves. But again, even if it's an avatar of yourself, it's still a considered representation of who you want to be. And I think when people lean into who they really are, the world becomes a little bit easier. Because trying to lie all the time is a lot of work. You’ve got to remember who you said to what at what time. If you're just being who you are, you can walk down the street and talk the same to anyone at any given time. It’s a gross simplification, but I think the path of least resistance of who you are is a great one to walk.

Yeah. I think that there’s something really important to observe here—that you and I are two people known for brand work, and we’re not talking about colors, and type, and photography styles. Because in brand, that’s important, but it is not what is most important. It goes much deeper than that.

Yeah, and there’s still so much that I want to learn myself. I’m 40 this year, and I've had all these years behind me, but I do feel like I'm just getting started. Like I feel like I haven't even scratched the surface of the stuff I'm going to do. You know? I want to start a family, I have no idea what that’s like. That's a whole different reality, as you know yourself.

So I know that I haven't even really seen a whole facet of life. And I also try to think about that as a concept creatively. I know there's so many ideas in my head of things I want to do and create an experience and accomplish. And I'm not doing it for other people or for external motivators. I'm just realizing that life can be really fun. And you're only here in this form for not that long. So I'm trying to really enjoy the most of it while also having gratitude and be humble and appreciative to people that you interface with as you go through your own journey.

Do you feel like you've honed in on a central purpose or driver for yourself?

Well, I think I was happy to turn 40 as almost like a halfway point because I do want to put a close to a chapter where I was driven by survival mode. It stuck with me maybe for too long where I was a very, very independent person, borderline selfish, where I felt I had to take care of myself. I had to take care of my sister, I had to take care of my friends. Everyone else, get out of my way. And I was just going to put my head down and work 12 hours a day every single day, seven days a week, 365 days a year for, I don't know, over a decade straight. No breaks, no anything. And it has taken me another decade to wean that out of my system.

And so, I want to start a family. I'm really excited for that. And I can't wait because I know the selflessness that I want to feel is there. And being married now—I'm thinking for two versus thinking for one, which is a new concept.

Professionally, I don't know. I feel and see this thing, a culmination of my work, that I think is going to take me 10 to 20 years to get to. And I think I have a lot of work to get to an understanding of people and concepts, to be mature enough to know how to do that. And I find that really motivating because it gives me a lot to focus on. I'm not trying to retire at this age or I'm not trying to do the same thing. Like I have something really big that I want to accomplish that I don't even know how to describe. But I know that I can barely see it, and I think I'll see it closer when I'm 50. And I think I can maybe start to realize it when I'm getting into my sixties, you know? So it gives me a lot of purpose in a really stretched out capacity.

That's so refreshing to hear. And I think it's going to be so good for other people to hear, to remember… “Oh right, we're going to be alive when we're in our fifties and sixties. We don’t have to peak now.”

Well, take that Blue Zones show on Netflix where you see centenarians around the world. They stay busy. You know, they're tending their garden, they're playing games in the community with other people. They are still working the farm. Like, you’ve got to have purpose. You’ve got to have something to get you out of the bed every day and solve problems to ward off the bench and other things that can really hit us when we get older. The more you can just use the body and use the brain. And that's where I think work is great outside of income. It's more than that. Work really is a sense of purpose and contribution.