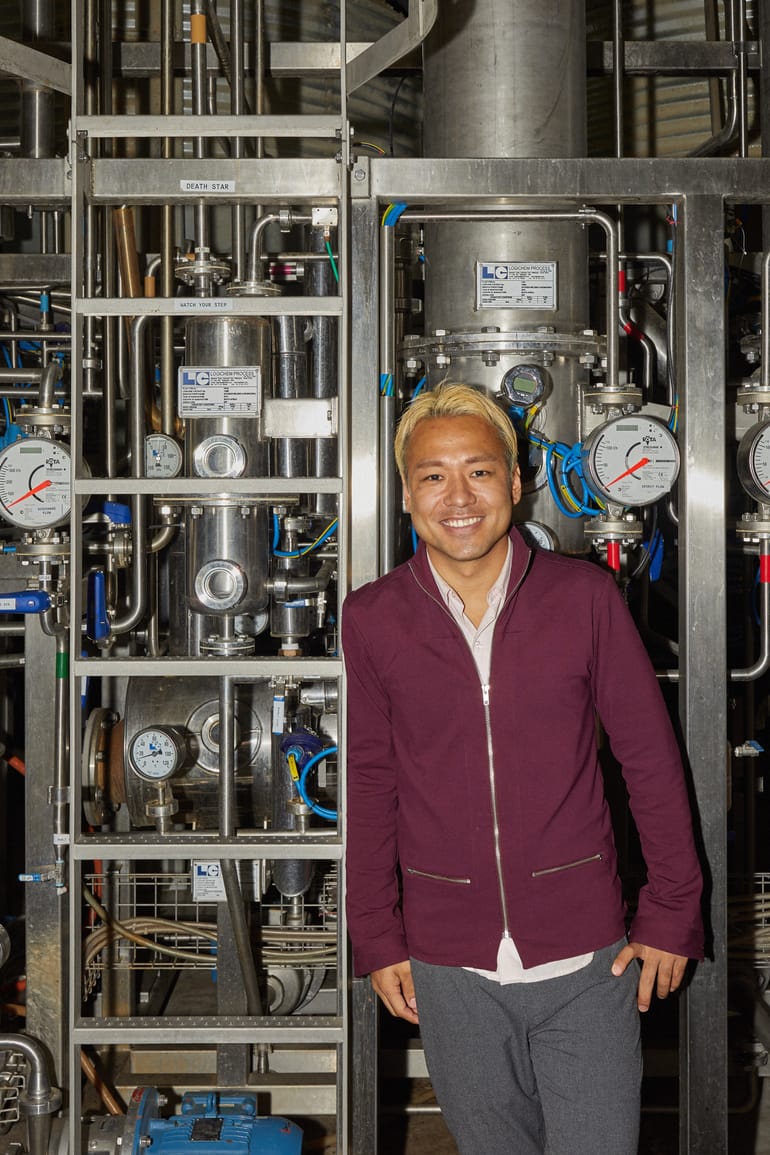

Evan Shapiro is an award-winning media executive turned independent media entrepreneur. Born and raised in suburban New Jersey, he did not have the family background or industry connections often deemed necessary to succeed in the industry. However, his decision to drop out of college and move to New York City to pursue theater set him on a path to remarkable success in media.

Evan ascended to become an Emmy and Peabody Award-winning producer, creating groundbreaking works including "Portlandia," "Please Like Me," and "This Film Is Not Yet Rated." He would eventually become a top media executive at IFC, Sundance Channel, Pivot, NBC, and Seeso, guiding these companies through the media industry's evolving landscape.

While in leadership, he found constant resistance to the idea to his recommendations that the industry would need to change. This reached a head on his 50th birthday, when he was unexpectedly fired from his own innovation lab at Comcast.

Evan quickly turned to writing, making his recommendations to the industry at large, instead of individual, change-averse executives. He now runs a successful independent media company, where he educates the entertainment industry through writing, podcasting, speaking, and consulting for the very conglomerates who wouldn’t listen previously.

Evan’s story underscores the importance of adaptability, resilience, and the possibilities that come with embracing change and new beginnings.

Hello and thank you so much for agreeing to chat with me today. I've been crying all morning, mostly because of you. That sounds terrible, but it's not. It's because of your story. We will get into that.

I'd love to just start with the beginning of how you grew up, what your family was like. I'm curious what that environment was like for you, and how you think it shaped who you were.

Yeah. So, I was born into pretty substantial privilege. My dad, he was an attorney. And my mom, for the most part, was a stay-at-home mom. This was in the early 1970s, and we lived in what would later be called a yuppie neighborhood. You know, it was like that movie “The Ice Storm”—a lot of hidden discontent under the surface. These young couples, eventually, most of them ended up divorced. And my father, well, he was pretty abusive. It was, unfortunately, a normal part of life for me back then. I was a pretty precocious kid, had my own challenges with maturity, just like any kid. But yeah, I was quite precocious. So, there was this sort of middle-class gloss, this veneer of normalcy that kind of covered everything.

And then, when I turned 11, my parents were the first in our neighborhood to split up. My dad, well, he kind of lost his mind. It was partly due to drugs, and maybe bipolar disorder—never really diagnosed properly throughout his life. And then, he just lost his grip in his early 30s. Suddenly, the privilege I had always known was pulled out from under me. My dad stopped making a living. He just ceased providing any financial support to our family, leaving us in a tough spot.

And my mom, well, she was left to fend for herself. She had to sell our house and move us to a wealthy suburb called Cherry Hill. But in Cherry Hill, we were on the poorer end of the spectrum. She started working full time for the first time in my memory. This meant I was pretty much left to my own devices after school, almost until bedtime, every day. I often had to take care of my brother, which I admittedly didn’t do very well. I was basically raised by TV more than anything else. My social life was limited—I had some friends, but not many. Television shows like “Gilligan's Island,” “Star Trek,” “The Brady Bunch,” and cartoons like “Ben and Jerry” and “Bugs Bunny” became my way of learning about the world.

As for my father, his presence in our lives was inconsistent over the years. My mother worked incredibly hard and did the best she could. Those years, especially through middle school, were very interesting, to say the least. When I got to high school, I really started to find myself. I joined the theater group and instantly felt at home with the theater crowd. There, I built many strong friendships and began to understand what I wanted from life. I was deeply involved in theater and various other arts activities throughout high school.

After that, I barely managed to attend college before I dropped out and moved to New York to pursue a life in theater.

Now I’d like to talk about your entertainment career. You've achieved what many would consider conventional success, right? You’ve won an Emmy. You've worked on well-known projects and at well-known media conglomerates. Yet I’d still describe your career as unconventional. Can you tell us about this path, and how you navigated it?

Yeah, yeah. Some of it is purposeful, and some of it just happened by accident. I don't think many people truly grasp how important it is to have industry connections to succeed in entertainment. Look at most successful people in our industry, their parents were often involved too. Like Robert Downey Jr.’s dad was a director. And knowing people, and being related to them, it plays a big role in how you enter the industry. I had none of that. No contacts, no college degree. I moved to New York with dreams of writing and directing, but ended up doing that in my spare time while working other jobs in the industry during the day.

Independently, I directed and did art projects, pieces of theater, downtown stuff. Then I worked mainstream, for Cameron Mackintosh—known for Phantom of the Opera, Cats. I quickly became head of marketing at the New York Shakespeare Festival and Public Theater's Shakespeare in the Park. My boss, George C. Wolfe, a talented director, gave me freedom, and our theater really took over the town. At 27, I started my own marketing agency for theater. This meant giving up my creative work—I wanted to be making my own stuff—but I decided to channel that energy into being the best marketer. I sold the agency, moved into television at Court TV and then IFC. In less than a year at IFC, I became general manager.

As general manager, I got to greenlight and produce projects. Being able to choose projects is an amazing opportunity, unlike an independent producer who waits for someone to buy their idea. I worked on projects like 'This Film is Not Yet Rated,' being more hands-on than most TV executives because it was a small network. “This Film is Not Yet Rated”—I named that film. I chose the animation company. For “Portlandia,” it is named what it is because I convinced Fred and Carrie to set it in Portland. My involvement was different than typical senior TV executives. If I were at a bigger network, perhaps it wouldn’t have happened like that. As I got promoted, I ran two networks, Sundance Channel and IFC, making stuff like “Brick City” about Cory Booker and Newark. But then my role became less creative, more about PowerPoint presentations and sales, so I left.

“There was a huge white space for original thought about where the media ecosystem was going. I always knew this but didn't understand how to capitalize on it. Then suddenly, I didn't wait to decide how to capitalize on it; I just started filling the void, and it capitalized itself.”

I went to Participant Media, worked on projects like “Please Like Me,” “HitRecord with Joseph Gordon-Levitt,” then I went to NBC, involving myself in various productions. My involvement was deep because I was always in smaller, independent settings, below the radar, allowing me to be involved at a level not common for people in my position. I’m not a fan of mainstream, like reality shows or The Voice or anything like that. Nothing against them, but they are not my thing. I prefer smaller, independent stuff, which turned me into an artist-producer, an artist-executive. Artists liked working with me, programming executives maybe less so because I was hyper-involved. And I always loved marketing, staying involved there too.

So, part of my career was self-directed, part was being in the right place at the right time, and part was just the circumstances I found myself in.

When you talk about yourself breaking industry norms, I can't help but think back to your earlier point about how many in this industry have parents who were also involved. Do you think that your industry has a hard time changing because of generational dynamics?

The people in power inherited the rules. You can see the dedication to old-school Hollywood, especially in the two strikes this year and how they were mishandled by senior executives. There's this mindset of 'We’ve always done it this way, it will always be done this way.” That rigidity was frustrating. It's one of the reasons why things didn’t work out for me at NBC and AMC Networks—back in 2011, I was advocating for turning Sundance into a streaming channel, but the resistance was intense. The argument against it seemed to be, “Why would we facilitate the demise of an ecosystem that's paying us?” My point was that this system is dying anyway, and all they were doing was delaying the inevitable. But no one wanted to hear that.

At NBC and Comcast, I was brought in to disrupt, but once I started, people hesitated, saying, “There’s a lot of money here. You don’t understand how this works.” I saw it differently. That revenue was going to decrease every year from then on. They insisted it was sustainable, but each year since then, there’s been less money in the ecosystem. There's definitely an attachment to the status quo. For example, Brian Roberts is a second-generation owner of Comcast, and Steve Burke grew up with a dad who ran ABC. Most of them in the industry grew up in it, but what they fail to see is the growth curve of television and film from the early '70s to the 2000s. It was like a natural growth spurt, but they took credit for it as if they had caused it.

What they don't realize is that the growth from the '80s through the early 2000s was the natural progression of an industry fueled by cable, which funded everything. But in the early 2000s, this growth began to slow, and none of them wanted to admit that their achievements were more a result of organic growth, not their genius. Admitting that this era is ending and that they had little to do with the growth is something very hard for people to accept.

Yeah. I mean, there's so many parallels to my world.

I know. It's like it's the same thing in tech.

You can over credit yourself for the good times and you’d be wrong to assume that your strategies are going to work forever.

Right. Exactly.

Yeah. Well, so I'd love to segue that to this peak of your career where you were, you know, in the big offices at Comcast. You were brought in to build an innovation lab. Then you were fired. Then you decided to go independent. I'd love to talk about that.

Yeah. I mean, I wish I could say it was my idea, but it wasn't.

So, on my 50th birthday, I was fired from Comcast. They just pulled the plug on my whole enterprise, and it was a very public thing. I will say, though, they paid me very well to leave, which has happened to me a couple of times and has been very fortunate. Also, the other fortunate part is that I got shoved out the door right as the whole thing started to slide into decline. It’s gotten messier and messier each year since then. So there's a lot of good fortune in that.

But, on the other hand, it became very clear to me at that moment that, as a middle-aged white dude, my time in those roles was up. It was also clear to me that I'm just not a great corporate citizen, and I had probably made the money I was going to make from big corporate media. I should count myself lucky and figure out what to do next. It wasn't super easy to figure out, but it became clear that rather than servicing larger brands, I could build a brand around my reputation and skills, which are pretty unique. And if I was smart about it, I could do as well, if not better, because I'd be happier than relying on people I thought were idiots. I knew they were wrong, yet I kept going back to them for jobs. So part of it was just telling myself, “If they are that wrong, why do you keep working for them?” And the answer was never really the right one. It was often about the opportunity, but often it was about the title, the power, and the prestige, not the actual job satisfaction.

It was at that point, I said to myself, “If you believe in yourself this much, you should be able to make it on your own.” It's not about a title, a company name, flying first class, or having the money to greenlight a project. It's about having the right ideas and knowing how to communicate them. So I focused on creating, which to me means writing now. And then I just started writing every day, following where it led me. The more I put these concepts out there, the more opportunity came back to me because there's a vacuum of original thought in my industry. More so than most, I'd say. The last big innovation in media was Netflix streaming content, and that was almost 20 years ago. Everyone else is just copying that. The only innovations in the last ten years in media have come from Apple, Amazon, and Google, and even those aren't groundbreaking. Apple is just incorporating what Netflix and Spotify are doing into their phones.

So yeah, there was a huge white space for original thought about where the media ecosystem was going. I always knew this but didn't understand how to capitalize on it. Then suddenly, I didn't wait to decide how to capitalize on it; I just started filling the void, and it capitalized itself.

“Since leaving the industry, I've been embraced more by it than when I was inside.”

You talk about presenting original thought in your corporate environments, and you getting pushback generally. Did you find that when you expanded your audience, you suddenly found a different reaction to the same behavior?

What's fascinating is, once you remove yourself from the cult, the dynamics shift. Inside the cult, if you're the dissenter, they burn you with the stake. But the moment you step out of the cult and start expressing the same things, only now without the censorship and in a place where more people can hear you, they actually listen. I don’t get any pushback, which is surprising. The same companies that fired me now invite me back to tell them what to think. It’s like that Groucho Marx saying, “I would never want to join a club that wouldn't have me as a member.” You listen less to the people you live with than to the people who visit from outer space.

Once I left and chose LinkedIn as my platform, things changed. LinkedIn is a fascinating forum for publishing provocative thoughts and controversy. It’s led to a lot of conference invitations. Being a professional provocateur, I get invited to stand on stages and say provocative things because it's entertaining, and it expands your audience. The industry gains momentum from allowing someone to come in and throw grenades at it. It's entertaining, generates clicks, and other things.

But there's another aspect. Knowing everybody in these companies, having conversations with them behind closed doors, I know what they're thinking. Often, I'm just saying what they're thinking themselves. Since leaving the industry, I've been embraced more by it than when I was inside.

That’s beautiful.

If you don't mind, I would love to change the subject to your personal life, and the recent medical issues that you’ve had. I was reading what you wrote about your situation this morning, and I cried and cried because man, life is fucking hard. I think everyone who's reading should read the piece you wrote, and I will link it here.

But you talk about having cancer. You talk about almost dying from complications from cancer. And you not only gained such a beautiful perspective from it, in my opinion, but you're also sharing that perspective through this industry medium that you've built for your community. It was just beautiful. I'd love to talk about this whole thing if you’re willing.

Yeah, I mean, I've had difficult moments in my life. But this year, it really educated me on how un-challenging my life is, you know? Like, my dad, he whacked me around a bit as a kid. But let's be honest, a lot of dads have beaten a lot of kids over many years, for decades, centuries even. So I'm not the kind of person who points to that as a cause or anything other than, well, it's awful, and now it's over. But from that point, I dropped out of college. That should have been the end of my professional opportunities in the world. But it wasn’t, and that’s partly because I'm a straight white dude in the world, and I ended up getting more opportunities because of that.

Yeah, but don't undersell yourself.

You know, it’s more so about me about appearing relatively normal in the industry, and the massive benefits that can bring you. Life’s been easy for me, whether it was marrying the right person young and having two healthy kids in quick succession, or finding one great opportunity after another, each better than the last. I entered the entertainment industry while it was on a steep incline and rode that wave, making way more money than I ever expected. Along the way, I'd get upset, angry at people, worried that losing a job would be the end of my career, but none of that turned out true. Then you get diagnosed with cancer, and it’s like, “Whoa, this was not expected.” But even with cancer, I got a “lucky” kind, very treatable. I joked that if you have to get cancer, this is the one to get.

Just when I thought things were looking up, attending my brother’s wedding, I started treatment and it was going well. Then suddenly, my body just decided it had been too easy for too long. Being in the hospital, facing doctors who have no clue what’s wrong, that's scary. And the medical profession, it's dehumanizing. You're just a birthdate, a code to scan, a body to stick needles into. I realized how fortunate I was to have health insurance and thought about those who don’t. That's when I really gained perspective on my life. No real challenges in my 56 years until then.

Then reading about thousands losing jobs in my sector, lying in the hospital bed at four in the morning, I felt grateful I didn’t have a boss, wasn’t in a corporation cutting costs, not in a Game of Thrones office environment. I’ve been in situations where family emergencies made me worry about job security. I wrote about this, not so much about me, but as a gateway to discussing appreciating life, not putting the job first. That’s the quintessence of my artistic identity. That article, the emotional reactions I've received from it, have been more gratifying than any other creative work I’ve done, even more than the Emmy and Peabody sitting over my shoulder.

I wish I didn’t have to go through that hospital ordeal, but I’m also kind of glad I did. It showed me I have the toughness to get through most things, and for that, I’m grateful.

Yeah. Thank you for writing it. I mean, it knocked me out.

And this is all relatively recent, right? The last couple of months. Obviously your perspective was changed by that experience. Would you say it is easier or harder for you to do the work that you do now, after what you've recently been through? Has it changed how you think about your work?

I mean, first of all, yeah, it's changed. It's changed the amount of hours I work in a day, which are less now. And it's made choosing what I work on easier. I don’t think it’s made the actual work itself easier or harder. The work I do, especially writing, comes very easily to me. Every time I think the well might be dry, I go to it and there’s always something there. I’ve been very fortunate to have an endless source of content in my head. So, it’s made making choices much easier. It's also changed what gets me upset. Nowadays, it’s really hard for me to get upset about anything work-related. I might think, “That's unfortunate,” but that’s about it.

Simultaneously, since my diagnosis this summer, I started practicing mindfulness and meditation. This has created a gap between me and my emotions. I'm not emotionless—I'm actually very emotional. But now there’s enough of a buffer between feeling an emotion and reacting to it, making it harder for me to get upset, worried, or even care too much. I care about my work, sure, but if I don’t get a client, or I lose one, it's like, “Okay, another window will open.” This whole experience has made the choices I make in my professional life substantially easier than they were last spring.

Something that's come up for me in a lot of these conversations that I've had is nihilism. There seems to be this wave of nihilism hitting everyone. I mean, Gen Z is the king of it already, but for us elders, it's hitting us too, right?

And I don't necessarily get nihilism from you. If anything, I get you just being you leaning harder into your ethos of, “I'm just going to do more of what I want to do.”

I mean, I'm the opposite of a nihilist. I'm an optimist, maybe too much so for some. But no, I don't see the end coming. I do care about things, about people, even though there are things I can't change. At the end of the day, my faith in who I am and in the people I surround myself with is strong. I lean heavily into my community, which isn’t a large group, but it’s important to me. I focus on nurturing those relationships more than anything else.

So no, I'm not buying into nihilism. I do feel frustrated about people doing harmful and irrational things to our planet, whether it's the ongoing conflict between Israel and Hamas, or the misguided priorities we have here in the United States. It upsets me, our inability to see the bigger picture. But I don't think it's the end of everything. It's the end of one era and the beginning of another. History has shown us this. People often forget how dark the 1930s were, how bleak the first 40 years of the 20th century were.

“You can try to wrestle with these changes, or you can observe them, learn from them. I believe that by doing the latter, you can at least find some peace of mind.”

We're experiencing similar difficulties now—from 9/11, through Covid, the rise of fascism, to the conflicts in the Middle East. These are like growing pains for the planet, part of a generational cycle. We grow, we shed skin, and then we grow again. It’s a natural progression. You can try to wrestle with these changes, or you can observe them, learn from them. I believe that by doing the latter, you can at least find some peace of mind.

Yeah. I have a somewhat similar question that is also somewhat selfish.

So both of our industries seem to be struggling right now.

I am also feeling particularly triggered today, not only because I've been crying over your story, but it was just announced this morning that Sam Altman is rejoining OpenAI, after a week of absolute chaos in the industry. It's just been such a debacle. And it's revealed, again, that there is often incompetence and even malice in the most powerful positions in our industry.

And, you know, I had my own journey as an entrepreneur, which was pretty epic. And I saw a lot of bad behavior, at levels that I could have never imagined, from people in positions of power. It was, and still is, really difficult for me to accept.

I wrote a little bit about it this morning in my journal. I'm just like, “Man, why is this triggering me so much? Like, we had Trump, we've had malicious, incompetent leaders.”

But then I figured out what it was. I’ve never believed I could depend on a president for my safety or livelihood. But I did believe in Silicon Valley. I’ve been here for 15 years. For me, Silicon Valley was like the parents I always wanted, you know? Silicon Valley was the thing that rescued me from the life I had, and it was going to bring me abundance and stability and purpose. I was going to give my life to it, and it was going to take care of me. And it has in many ways. But over the last couple of years, I’ve realized that mom and dad are not safe or stable.

Mom and dad are on drugs.

Yeah, they have revealed themselves. And I'm finally mature enough to see it.

So my question is... You’ve been on the inside, and you are now participating in the industry as an independent. You’re sitting here watching your own industry hit a wall. How do you stay motivated to stay involved?

My relationship with the industry is complicated, similar to how I have an interesting relationship with my parents. I used to seek approval from the industry, replacing the approval I craved from my parents. When I didn’t get it, it upset me. But now, after seeing my metaphorical parents and the industry for the abusive, incompetent addicts they are, I actually enjoy reporting on it. It’s like watching Godzilla and Mothra destroy the planet—it's not real, so it's entertaining. Just give me the popcorn.

I watched the Altman thing, wrote about it, and said it's clearly a bubble. Watch it unfold, and you'll see.

Once you detach your self-worth from your connection to these people, you can step back and observe it all without getting emotionally involved. And, this may sound messed up, but the more they fight, the more money I make. The more the ecosystem is in flames, the more people look to me for a hose.

In the last two years, many people have been shown the door in your industry with better paychecks than those in mine. There’s a moment to sit back and think, “Well, we got out in time.” There’s going to be an industry in picking up the pieces, whether as therapists, street cleaners, whatever it is. There's too much money floating around. Tech and media aren't going anywhere. They’ll be rebuilt in a different form. When Apple, Google, or Amazon becomes the dominant force, they’ll still need someone to tell them how it works.

The key is not to tie your emotional well-being to the behaviors of people you know are messed up. The day you learn to detach emotionally is the day it all becomes more clear, more entertaining, and then potentially profitable.

Man. I spend a lot of time thinking about this stuff. All of the layoffs in my industry, and that there's really no venture track anymore, not like we had. I’m not totally sure people realize that yet. And all these people have nowhere to go because the market's contracted and it's changed forever.

But there are places to go. It’s just that people in our industry often see things too linearly. It's not linear. There’s an entire universe out there. Unemployment in the U.S. is historically low. There's a lot of money in the American ecosystem. You just have to disassociate from the traditional geography, mindset, and power structures.

I spoke with someone today who's been in media her entire career, working out of Denver. She's considering a shift but wants to stay in media and in Denver. I asked her which was more important: living in Denver or staying in media? She chose Denver. So, I suggested looking into a different industry. The media industry is shrinking. Even if she found an open position in Denver or L.A., she'd be competing with thousands for it, because there just aren’t many jobs. Yet, Denver’s economy is one of the fastest-growing in the U.S., with lower unemployment than the national average.

When I coach people about their careers, my first question is always about their top three priorities. Often, these priorities don't really align with a specific job title or industry. They're usually financial—needing to pay bills, wanting to live in a particular place, or desiring time with family and not having to commute daily. None of those are dependent on staying within a specific sector.

Focus on those three priorities. Once you do, your aperture widens significantly. There’s not a single aspect of the world that doesn’t involve tech. So, if you're in tech and concerned about your career, consider stepping out of tech and then applying your tech skills in a different sector. Whether it’s automotive, publishing, television, medicine, education—all these industries need the expertise that people in tech possess. The key is to get out of the Silicon Valley mindset, both mentally and physically.

“If you're in tech and concerned about your career, consider stepping out of tech and then applying your tech skills in a different sector. Whether it’s automotive, publishing, television, medicine, education—all these industries need the expertise that people in tech possess. The key is to get out of the Silicon Valley mindset, both mentally and physically.”

Oh, man. It's what everybody, including me, needs to hear. We, more than anything, just have to let go of how we thought things would work out here.

Yeah, and you guys, perhaps even more so than the media, are so addicted to the hierarchy, the pecking order in Silicon Valley. It’s all about where you stand next to your peers, measuring your self-worth by how many stock options you have, what your title is, which company you’re with, where your office is located. And boy, that’s really dangerous. Pulling yourself out of that rat race is step number one. It’s like leaving a cult. It really is. And I don’t think people realize how deep the tendrils of a cult like that run, until they truly extricate themselves from it. And often, that means physically removing yourself from the coffee shops and yoga studios where everyone congregates. It’s crucial.

Yeah. And similar to what you said earlier, while it was awful, I'm so glad that I already had to go through it.

And not having to go through it in real time right now.

Yeah, it's a blessing. Anyway, I have a couple of final questions for you. Again, they're all stemming from this one post that you did, which was so amazing and everyone should go read it right now.

Related to what we were just talking about, you write verbatim: “If you are out of a gig or facing a layoff, the worst thing you can do right now is blame yourself. The best thing that you can do is to invest that very energy into finding yourself.” Could you expand upon that?

Yeah, a conversation I had with myself on my roof on my 50th birthday—the day I got fired—was probably the most important one I've ever had with anyone. It was about pushing myself to ask, “Who do you want to be?” rather than just, “What do I do next? Where do I get my next job? How do I make a living? What do I tell people?” Those thoughts were always running through my head. But then I managed to step back and ask myself, “Well, who do you want to be? You have maybe 20 more years in your career, from 50 to 70. Who do you want to be during that time?”

That's crucial. It’s not just about what you want to do, but why you want to do it—what matters most to you at the end of the day, and what do you want to get out of your efforts. Asking yourself these questions is far more important than just reflecting on what just happened. You should learn from both your failures and successes. But at this moment, the essential questions are “What do I want to do? Who do I want to be? Why do I want to do these things?” The “why” is particularly important. “What matters most to me?”

No one dies happier because they spent an extra 40 hours at work each week. They die happy because they've left behind something they're proud of, they're surrounded by people they love, or they've helped build things that outlive them. But it's really hard in this moment to understand what that will ultimately be until you figure out who you want to be, what you want to do, and why you want to do it. These three questions are crucial, and surprisingly few people ask themselves these at major turning points in their lives. It's especially important when you're no longer in the job you thought you'd have forever, when you don't have that safety net, and you're out of the hierarchy. Instead of wallowing in “Oh, I messed up,” it's about asking “Without all those trappings, who do I want to be?”

All right. Well. My last question would be, you know, for the large population of my industry that is going through a career and identity crisis right now. Do you have any last wisdom for this group?

Yeah. I mean, we now live longer than humans were originally supposed to, and because of that, regardless of your current age, you’re likely going to have four or five very different parts to your career. I’d even argue that a healthy career should have four or five diverse phases. You don’t have to switch from being a doctor one day to a plumber the next, but different sectors, roles, cultures, companies. I started in theater, and what am I doing now? It’s a testament to how careers evolve these days.

Many people facing what they consider an existential crisis from losing a long-held job need to understand that it’s about ending one chapter and starting a new one. It’s not just about finding the next job or wondering how to make a living. It's asking, “Who do you want to be?” This is the start of something new, possibly a fresh start or a significant departure from the past, not just for your own enjoyment but for growth. Think about it: eating the same sandwich every day would get dull. This is your chance to change your diet, which in turn changes your brain, your outlook, and introduces you to new experiences.

“People facing what they consider an existential crisis from losing a long-held job need to understand that it’s about ending one chapter and starting a new one. It’s not just about finding the next job or wondering how to make a living. It's asking, ‘Who do you want to be?’”

This is a big, huge box under the Christmas tree with a bow on it. You have no idea what's inside, but aren’t you excited to open it? Most people need to view this moment as an opportunity. It’s not about identifying with your job title or paycheck. Consider the benefits and privileges you still have—friends, family, some money in the bank, your talents and intelligence. These don’t vanish because you lost a job.

The key is to be grateful for what you have and look at this next chapter as an exciting mystery. You’re about to unwrap something potentially wonderful. That’s how you should approach this—not with dread, but with anticipation and curiosity.

Fantastic. Thank you. I very much appreciate you being so open and forthcoming in this conversation. I am glad you are doing better.

Thanks so much. Appreciate it.