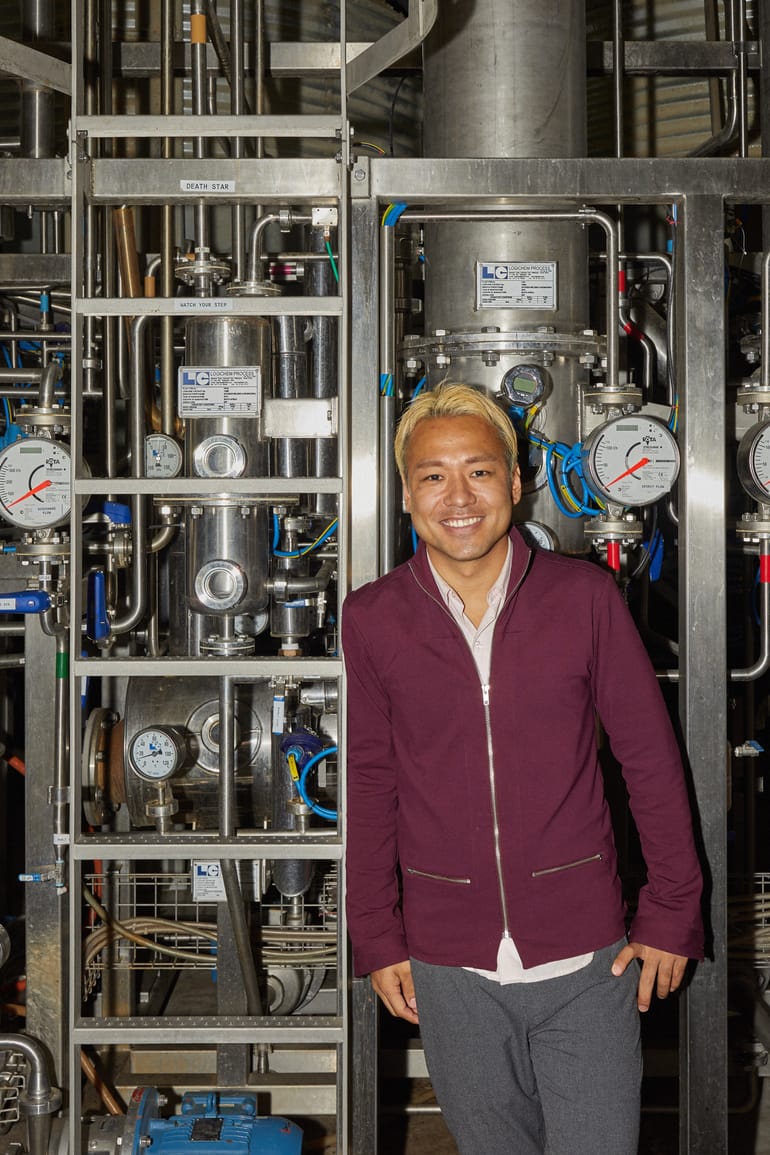

On Bootstrapping, Parenting and Serving Your Community

Melissa began baking at seven years old with her grandmother. That interest eventually led her to opening her first bakery in Denver at age 23. After selling her first business, she went on to direct large pastry programs on the East and West Coasts for some of the leading names in the baking industry: Bien Cuit (New York) and Gjusta (Los Angeles).

She eventually moved to California to work at the three-Michelin-starred SingleThread with her husband and chef, Sean. Not long after, she was invited onto national television to participate in The Food Network’s Holiday Baking Championship. She ultimately won the competition.

Unfortunately, the pandemic swiftly hit, making any sort of publicity tour impossible. Instead, stuck at home, Melissa and Sean began a “Porch Pick Up” bakery from their living room in Healdsburg. Their popularity from this program led to giant lines through the Healdsburg farmers markets where they also sold their goods.

In 2020, the couple opened their Quail & Condor retail bakery using the funds from their farmers market sales. They then opened Troubadour Bread & Bistro in 2022. Both spend their time educating their team and community on high-level technique, sustainable sourcing and production, and engaging in philanthropic projects. They live in Healdsburg, CA with their two young boys. (Notably, the oldest was my daughter’s boyfriend in preschool.)

Hi Melissa. I'm excited to chat with you. We share a physical community in Healdsburg, but our business backgrounds are very different. I come from a Silicon Valley community that's passionate about impacting the world through the Internet. But more and more, I'm finding myself wanting to learn about different business models, especially those whose market is a physical community. I’d also like to talk about bootstrapping, which you know a lot about.

The pandemic has changed a lot for a lot of people. It's made us reevaluate what we want from our work. Instead of just chasing conventional markers of success, there seems to be a universal shift towards seeking deeper connection, enjoying our work, and appreciating the craft. When I look at your business, I can't help but admire how you've blended craft with a connection to your community. It's something I would love to discuss.

Thanks, Helena. Your introduction made me think about a recent experience. Yesterday I attended a branding panel with a diverse group of speakers. A recurring theme across all of their backgrounds was the importance of introspection.

You touched on the point that work isn't just about conventional or financial goals; it's about building something with intention. This resonates with me deeply as a founder. I always go back to, "What are my personal goals? How will that shape my business? And what kind of impact do I truly want to make?”

I might exaggerate a bit here, but I've always seen myself as someone with not a lot of talent. If baking is it, then I embrace it with all my heart. It's a passion that has always blended my personal and professional worlds.

I'd love to stop you there because I’m surprised to hear you say that. Part of this project is diving into people's internal wiring, exploring where it comes from and discussing how it impacts their work. And to hear you say “I don't have much talent” makes me want to just stop and shake you. (laughs)

I used to think I only had small talents, but I've come to realize that maybe I am actually talented. Recently, I've discovered my knack for photography and found that I have an eye for creating floral arrangements. These skills have a distinct style and brand that's truly a reflection of me. It's been fun to learn these things.

Again, I want to stop you there because… where did you learn that being really good at baking is not enough? Where did you learn that you might need to be good at ten things instead of one thing? Because you've done quite a lot with your one primary talent.

I honestly think it's my upbringing.

Ok. Let's go there. What did your parents teach you about work and value?

My mom and dad had me without being married, and my mom remarried to my stepdad when I was just under a year old. Throughout my life, I've had a loving relationship with my birth father. But I've noticed that their generation, regardless of which parent it was, seemed very results-driven. They always focused on "What can you bring to the table?" I'm thankful they exposed me to various experiences, and whenever I showed an inclination toward something, it was expected that I'd pursue it further.

That said, when I was in grade school, every career idea I shared with my birth father was met with what he thought was a better alternative. If I said, "I want to be a cartoonist," he'd respond, "How about an orthodontist?"

And then there was my mom. She had her own set of expectations. She emphasized the importance of appearance: "You have to be pretty, you have to be thin." And she always said, "You need to find a good man who earns well." She never presented family as a choice. It was more, "When you have kids" rather than "if you have kids." And honestly, I never questioned it.

My birth father was always a hands-on person. I have memories of us painting parking spots at his State Farm office parking lot. He instilled in me the value of doing things myself. That's probably why, when we needed floral arrangements at one of my restaurants, I thought, "I'll handle the floral." Or when we required product shots, even though we have a professional photographer, I often felt the urge to step in, especially when she's not nearby. Instead of troubling her every time there's a special, I would work alongside her, assisting and learning. She taught me a lot, even helped me choose a camera. Now, I can take my own product shots. I believe this hands-on approach, largely influenced by my birth father, defines how I manage my businesses.

The vision I have comes from my stepdad. From a young age, he instilled a sense of fearlessness in me. Very "Go on, fall, knock your teeth out.” For him, everything was an experiment. He believed that there's no use getting upset or emotional about outcomes when you don't know what's going to happen in the first place. And he'd often ask, "What if someone else does it better than you?" All of this influenced what drives me.

My mom has this tenacity where she'll push through anything to achieve what she desires. I see a lot of her influence in me, especially when I opened Quail and Condor; it felt 100% like channeling my mom's spirit. There are many positives from their influences, but because of their generation's mindset, I constantly grapple with questions like, "Am I ever good enough? Am I training and leading my team properly? Am I earning enough? How should I present myself in photoshoots—as the real me or a dolled-up version?" There's a scene in the Barbie movie where America Ferrera delivers a monologue, and it perfectly captures these whirlwind thoughts that often flood my mind in these moments.

It ties back to what we were discussing before we started recording—that Ted Lasso episode you'll eventually watch, and this notion of "fuck you and thank you” that a player has for his dad. Our parents unintentionally harmed our generation in certain ways. We'll do the same to our own children in ways we can't even foresee. But often the very things that hurt us come with silver linings that end up benefiting us in one way or another.

Right now in my life, I'm trying to understand how these challenges have been beneficial to me. I wonder if I can continue benefiting from them while shedding the negative belief that drives them.

Absolutely. It's a balance, right? How can we teach resilience and tenacity to our children without subjecting them to the hardships we faced?

Yeah, but, you know, I'm trying to think of an example where things aren't weird and hard for kids already. You know what I mean? Like kids want to be in our arms 24/7 and they can't be, right? We have to remember that, by default, our kids are struggling with their deepest desires not being met.

I remember the first time I heard this kind of concept brought up. It was in a Longform interview with Cheryl Strayed where she was saying, “I am who I am because of the hardships that I went through. My upbringing was incredibly difficult. And it's made me who I am, and it's given me all these gifts, like strength and resilience. And here I am today, and my kids are having lunch at Oprah's house. And so how do I manage parenting knowing”—and I'm probably butchering this quote now, sorry Cheryl, if you ever read this—“How do I raise my children in a way where they have character, without manufacturing any unnecessary hardship for them?”

I've been reflecting on this lately. I want my children to understand empathy and recognize that there's always work that needs doing. These principles are deeply important to me. I want my kids to understand the significance of being considerate of others. I also want them to see that genuine rewards aren't always material. I want them to focus more on inner rewards than on monetary gains or physical gifts. I'm hoping to teach them that when you do good, good often returns to you. Life will inevitably bring challenges to everyone, and it's crucial to understand how to work through the difficulties.

You know, I had a recent realization about parenting and how much it teaches me about myself. For example, I was finding myself irritated at how much my daughter was asking me to buy her non-essential things when we were out and about. But then I started to notice that I was buying myself non-essential things all the time. This was a revelation: If I expect certain behaviors from her, I should be working just as hard to examine those behaviors in myself.

100%.

And that's this amazing opportunity that parenting presents, I think. And even being a boss, there's so many parallels. If I'm seeing a behavior that I don’t like, whether it’s a kid or an employee, taking a moment to be like… Well, I can't necessarily control their behavior, but is it possible that I’m modeling this for them without realizing it? I've got to focus on that first, or else I'm a hypocrite.

I'm experiencing this with my older child. Recently, we were playing in the plaza, and he was thoroughly enjoying himself. But we had a dinner reservation, and when it was time to go, he became noticeably upset. He struggled to express his feelings. I took a moment to reassure him that I'd be present and engaged during dinner, not just chatting with my friend. I knew he was looking for that reassurance. His mood instantly lifted.

I've come to realize that, whether dealing with children or even employees, clarity and reassurance can make a significant difference. It can be intimidating for them to voice their feelings or concerns, regardless of their age.

Yeah. We have to realize that the power dynamic is the same for both. We have to be the ones modeling behavior and communicating and providing a sense of reassurance.

I’d like to take a journey back into what led you into this field in the first place.

I think once my parents accepted that I wasn’t going to be a doctor, they came around and ended up being very supportive. And my stepdad has always been that way. Anytime I wanted to make jewelry, my dad bought me the best books. I wanted to do glass cutting—my stepdad bought me all the equipment and he really invested in any of my interests. So when I told him that this is what I wanted to do, he was like, “All right, let's do it.”

After two years, I got my associate's degree. I was like, “Okay, I'm ready. I'm gonna open a bakery.” And he's like, “No, you're not. You need to go get some experience and grow up a little.” And he said that kindly. And I think that was smart because I also just wanted to be, you know, a college kid drinking with my friends. I did need to grow up a little. So I had multiple jobs and learned some things. Then I opened my first bakery in Denver in 2014.

And you were still so young, right?

I was 23. And I loved that. I am, like, really energized by being an anomaly. And that's just me being competitive. So I quickly got to a really high pinnacle in Denver with that business.

Did you find that it was fairly easy? Like you opened this bakery and it just… worked?

Yeah, it was relatively easy. Maybe that’s just for me to say because I became obsessed with every detail of opening a business.

I guess to me this makes sense. Maybe I’m oversimplifying, but if you're really good at making baked goods, your bakery will do well?

I knew I had something. I knew that what I did was very individualistic and something I would commit to. It was also something that I could train others to do. It's teachable. So I think I formulated in my young brain, okay, I can do this. And I learned enough from my previous jobs, doing wholesale and that sort of thing, how the different pieces of the business work.

Only having a good product doesn’t necessarily mean your business will do well. It became less about the recipes, I knew the food was always going to be great. But I cared a lot about the flow of guests and the pastry display. Language of service, flow of production, readability of the menu boards… I cared about all of the details.

You just kind of knew you had the pieces. You had the pieces and parts.

And I'm very much a puzzle person. You know, Marie Kondo says, “I love mess.” Mine is, “I love bottlenecks.” I just love unclogging bottlenecks.

That’s the job of a founder, for sure.

I’m good at it. I come up with all these different ways to figure something out. And I love actually collaborating with people, I love coming up with all the options and for them to pick, I know that any of them are good options because I did the work of figuring it out.

Okay, so you had this business, this first bakery, you're a little baby and it worked.

Well, it mostly worked. There were some operational things that I think I was too young to understand. I wasn't good at managing. I wanted to be everybody's friend. I never took a day off, because I was young and invincible. So I decided to sell the business for $7,000.

Wow.

And it was valued at, I think, $1,000,000 at the time.

What led to that discrepancy at the end?

I did payroll taxes completely wrong. So I am thankful that the sale of the business covered all of it. But I only made it out with $7,000. I spent that money quickly moving to New York. I think by the time I actually landed in New York, I had $800 in my bank account and I didn’t even have a bed yet.

So you leave everything behind and move to New York.

It was really healing for me to strip myself of everything, living super minimally, being in a place where I had total anonymity—I knew like maybe three people.

Did you have that awareness at the time—that you were purposefully getting rid of everything because you needed a change, or did you feel these choices were somewhat unconscious and you were just following an instinct?

I think it's both. As much as I loved Denver, I just knew that it was time for me to go. And I felt lonely because all my friends from college and my best friend had moved away. And so I'm like, “Man, I'm lonely. Okay, I'm out.” And then of course I go somewhere else that's even lonelier.

I thought I would make friends and I thought it'd be a little easier for me to get around. But it was expensive, so I couldn't really go out. I loved my job, but I worked in a place that didn't have a ton of people my age, and most of them didn’t speak English. I ended up even lonelier.

Isn't that interesting? I've experienced this in my life—when you feel lonely, the instinct is sometimes to turn even further away from the people you know. In retrospect, it's like… what was I doing? But maybe the subconscious thought is, “If I'm lonely with the people I'm with, it's almost easier just to run away than articulate my needs.”

I kind of learned that from my mom. Her initial reaction with many things is, “If this isn't working out, I’m out.” I didn't experience that from her, thankfully. But you know, my knee-jerk reaction was like, “okay, I'm out. It's not working. I don't want to be around this.” So I think it's a little bit of both.

Yeah. When did you meet Sean, who is now your husband and business partner?

We met in Denver right before I opened my first bakery. We were on the opening team for this big restaurant in Denver. And he was going through divorce. I was getting out of my longest relationship. And we and two other cooks just kind of banded together and we were all roommates. That was 2014. We all moved in together, and then he moved to Healdsburg in summer of the following year to work at SingleThread.

And you guys were still just friends at this point?

Just friends. We didn't even really hug, but we're just like the most compatible people in the world. We understood each other in all ways. It was so platonic for me, and for him—he was like, “I knew pretty immediately.” (laughs)

But you seemed to have this subconscious feeling that you need to be near him.

Yeah. So when I was in New York, he encouraged me to go. I mean, there were some things in between where he was like, “Do I move there? Do you wanna come here?” And there was like, hints of, like, do we need to be together? But I wanted to be alone and figure it out on my own. It's kind of like, when you go to college from being a high school student and you're like, “I want to go without a boyfriend because I just want to have no ties.” But when I moved away from him I almost immediately felt like, “Wow, that was sucky. And I miss my best friend.” I asked a couple of our mutual friends, “When you think of me and Sean, what comes to mind?” And they're like, “Oh, you guys love each other.” And my first thought was “oh shit, what have I done, by moving across the country from him”. And so maybe eight months later we finally talked and I poured my heart out and I'm like, “I don't know what this is, but I think I'm in love with you.”

And then I moved to LA, because I was like, “Can we just be in the same time zone? And let's just see how it goes?” We had been dating long-distance a little bit. Fast forward 6 months, and maybe a week after saying we wanted to have a family together, I found out I was pregnant. And it became a moment of reevaluation. I was at my dream job at Gjusta in Los Angeles. Sean was at his in Healdsburg. And when SingleThread got their three Michelin stars, you know, he didn't want to leave his job. And I was really excelling in my job. And so we did the pregnancy long distance.

Long distance pregnancy. That's so wild.

I know. It was actually pretty great. Like, we were so conditioned to it.

I think it's a testament to your security with each other.

I love that. Yeah, I trust him completely. And he trusts me, especially after what he's been through with his ex-wife. And it's nice that that's one less thing to worry about. So then right before our firstborn was about to come out, I moved to Healdsburg after going back and forth about who's going to move where, and I realized that ultimately there were physical things that Sean couldn't do if I was working and stayed in L.A. Like, I don't want to pump all the time. Sean obviously can't breastfeed. So I'm like, You know what? I want to not ruin my first experience with my first child. I can probably come back to this job if I really wanted to. And that was the first time I chose myself over work. And then I think it was honestly great to take time off too. I had no idea what it was like to take three months off in my life. Even between jobs, I’ve never skipped from one job to another without having another one lined up. So that was really good for my mental health and settling into motherhood. And then I joined Sean at SingleThread.

I mean, talk about a culinary institution. What an amazing way to come into Healdsburg to start out literally on top, right?

Yeah, you're right. So I was at SingleThread for a year. Towards the tail end, I started doing farmer's markets independently just because I liked baking at home. And as much as I love what they're doing at SingleThread, I was feeling limited. I was baking, like, ten little tiny things because I was the hotel baker.

What I love is seeing abundance. I love working an eight hour day and feeding 300 people. Making hundreds of units of something versus like ten tiny, detailed little things. But at the same time, I think the refinement that I got from SingleThread is what sets my work apart now at the bakery. So eventually leaving was bittersweet.

When did Quail and Condor as a concept appear?

Quail and Condor started over Instagram. I'm thinking: if I'm baking at home and I'm just practicing some stuff that I don't get to make at SingleThread, what is my outlet for offloading all of this stuff? Because I'm not going to eat twelve loaves of bread. I'm not going to eat two cheesecakes and so on.

I mean, I remember before I knew you, somehow ordering a cake from you and coming to your house to receive it. And you had babies crawling on the floor and you handed me this gorgeous, insane culinary piece of art just from your chaotic living room.

Yeah. Oh my God. And so, Instagram and technology has been such a great tool for me. Like, I think for some people, that's their bread and butter. For me, it's just a wonderful assistant for what I do. I'm thankful now that my business is very much word of mouth, and I kind of like it that way because it keeps it small and romantic. But yeah, in those times I was meeting people in the parking lot at SingleThread to pass off their orders. People would meet me in the parking lot and get bagels from me. (laughs)

That’s so funny. I love that.

Then I went on that baking show. That was really fun.

Right, on The Food Network. That’s a big deal! How did that happen?

I think the algorithm. So it was the same production company that does Guy’s Grocery Games, which they film here because Guy lives here in Sonoma. And I think the casting producers just happened to be on Instagram. And so because of their location setting, they saw someone posting a bunch of pastries on Instagram. So they hit me up on DMs and invited me to be on the show.

And that experience was awesome. I really love competing. TV's a weird one, but I love competing. My goal wasn't to win. It was just to at least make it to every round. And all I wanted to do was try everything. I wanted to be able to compete in every segment of the competition. Then I won, which was obviously helpful.

Then it aired right before the pandemic. All of that potential momentum suddenly was gone.

Yes, wow.

I mean, everybody locally, four years later, they're still saying, “Oh my God, the reruns are on!” Which is so sweet. But I just kind of wonder sometimes what our trajectory would have been if no pandemic had hit.

I feel like so many people can relate to that. That 2020 just completely derailed everybody's idea of the way their life was supposed to go.

At first, I wondered if opening a bakery in a pandemic was risky, especially in a time when people were becoming health-conscious. I had hoped our bread would be our main attraction due to its low cost and consistency in production. However, when COVID hit and the world turned gloomy, people sought comfort. To my surprise, customers began buying boxes and boxes of pastries. It felt like everyone wanted to indulge and find a slice of happiness. So, while I initially thought bread would be our mainstay, the pastries ended up paying the bills and becoming our most popular items.

I guess it can really be that simple: if you excel at making pastries, you'll sell pastries. At Haus, we learned that while branding, ingredients, and values are important, what ultimately brought customers back was the taste. In food and beverage, no matter what else you focus on, you can't forget that it needs to taste good.

I collaborate with a few brands that might not have the most attractive packaging or the most efficient fulfillment system. But they're deeply committed to the quality of their product, which truly stands out. If you nail that aspect, the other stuff seems to matter less.

Yeah. Again, it goes back to the idea that we all can overcomplicate things unnecessarily. Sure, it's good to have some sort of competitive edge, but, but we forget that sometimes the competitive edge is just tasting really good.

We hosted a baking competition last Saturday at the farmer's market. The winner presented these snickerdoodle cookies filled with apple pie. We had both a professional panel and a public vote. Discussing with the winner, Sean and I had these intricate ideas about how she might have created them. We imagined she precut, precooked, and froze components before assembling. But then she explained that no, she just made an apple pie filling, rolled it into a cookie ball, and baked it. Both Sean and I had over complicated it so much in our minds. Her approach was simple, yet the result was a near-perfect cookie. It was a funny, humbling and grounding moment.

It’s a good reminder that most things in life require much less thought than we think they do.

So you launched a bakery in your living room in a pandemic, and now you have multiple booming brick-and-mortars in Healdsburg. Can you walk us through bootstrapping to where you are now?

We used to operate at farmers markets where a significant portion of our earnings was in cash. The profits were substantial, and we managed to save a good amount. We found that our earnings from just one farmers market covered the overhead costs for a brick-and-mortar location. We also had a Kickstarter campaign to raise $20,000 for the big deck oven. Since our primary business wasn't operational at that time, we employed our friends to manage the counter and make coffee, compensating them through tips. We fed them and did whatever we could. I thought after one year that we were done being in start-up mode. I was like, “Great, we're a real business now. We are operating, we are in the green, we are good.” But once we started hiring employees so I could have some real days off, I realized, “Oh, there goes the money.”

We also realized we had a surplus of some bread. So Sean started doing sandwiches at Quail and Condor and it just exploded. And so fast forward, we were walking around the middle of town and we saw this other space. Sean and I were fighting a lot at the time because he wanted to treat the bakery like a Michelin star restaurant. For me, that was not going to work. I don't have time to tweezer pea sprouts on 12 croissants when I've got like 48 loaves of bread I need to finish. And so we were butting heads a lot. And when we saw that other space for Troubadour, I kind of felt like, okay, “let's have a baby to save the relationship.” We weren't going to divorce or split up, but the new space was to save our sanity. So that baby was Troubadour. And, surprise—that made things worse.

I mean, that's how it usually goes, right. Let's add a layer of complexity on top of the issues that we're facing—that'll fix it, right? (laughs)

For me, I just wanted him out of the building. I was like, Stop making this. It's not supposed to be here. Here's a box for you to go do that.

Like a man cave… that sells sandwiches.

But I quickly realized something—he wasn’t wrong in trying to treat the bakery like a Michelin establishment. We don’t have time to do super fine garnishes on every single thing, but yes on some. Most importantly, he was trying to show me how to treat everything with respect. Even cleaning out the dust pan or scrubbing the floor drains daily or deep cleaning the walk in refrigerator monthly. His pillars of operating were the greatest contribution and biggest lessons for me.

And it all turned out really good. And we figured things out. In situations where both of us have strong leadership qualities, it works best for one of us to take charge. So when he's at the bakery, I’m in charge. The same dynamic applies at Troubadour. And I like when he’s in charge there—it's refreshing to occasionally step away from making all the decisions. And these days I am really floating around and filling the gaps for everyone. Sean knows I can solve any challenge. And it is so empowering.

That's really beautiful.

As you enter this upcoming chapter of your life, what defines 'enough' for you? Do you have a set goal in sight, or is the joy of building enough for you? How do you envision your path?

I recently wondered whether I wanted to expand or consider wholesaling, and I realized the answer is no. Through my various ventures, I've come to understand what I don't want. Right now, our operation feels stable and established. We have all the necessary equipment, and while there's potential for growth, it's not my primary focus. My goal is to create a workspace I'd love to be in.

There are two distinct types of people I've noticed who work in the bakery. Some excel when they focus on a single medium and master that. For them, an eight-hour day with a singular focus is rewarding. Others, including me, prefer diversity. We enjoy dabbling in various tasks—from making buttercream to crafting granola and cookies. This variety in mediums is what keeps our passion alive. My vision is to have everything in one centralized space, allowing me the flexibility to choose my focus based on my mood and have the freedom to flop around.

But isn't that cool? It's full circle. You started this because you like making a thing. And you built this big, complex, beautiful ecosystem from that. And still, at the end of the day, the best part is still just getting to make stuff.

Yeah.

You really tapped into the nuts and bolts of bootstrapping, which is something that's kind of an elusive concept to a lot of the founder community. People tend to talk about it like it’s impossible because the money has to come from somewhere. And while that's a valid point, you don't necessarily have to start out wealthy. For example, I bootstrapped my creative studio by charging for 50% of my jobs up front, which is pretty industry standard. So, many businesses can be structured to pay for themselves right from the get-go.

I think starting small, like we did at farmer’s markets, is key. Using crowdfunding for an essential tool, like we used Kickstarter for our bread oven. Then we had Square, our payment processor, offer us a loan. The first loan we ever took out was $3,500. We used that money to put a dough sheeter in my dining room, so I didn’t have to roll croissants by hand anymore. And then, you know, you slowly build that up.

As Square watched us make more consistent money, the offers got higher. And I actually think those loans are very fair and it comes out of your sales, which is really helpful and it's a feasible payback amount.

But yeah, our family did not provide us any money to start the business. And Sean and I worked super hard and we used every resource we had—we had friends volunteer, which was amazing. We also had a skill set that people were happy to learn, even if it was for a month. But that help was just invaluable.

Something I think that gets glossed over is those moments that were borne of you needing help—they make for such amazing memories. Like the fact that you were able to bring the community together to help you, and that they were excited to participate and learn, and help you solve this puzzle of how to grow with no minimal resources. Those moments are some of the most special.

Absolutely.

I'm curious—where could, hypothetically, your community support you now?

Wow. That's a big one. You know, this reminds me of an experience I had when I was younger. I worked at this ramen place in Denver, kind of reminiscent of Momofuku. I was there for a good chunk of time, almost three years. Initially, I was cooking—and it was an open kitchen—and then I decided I wanted to serve. So, I started hosting up front. And it was so weird how differently the same patrons treated me. They’d sat at my bar, right in front of my cooking station. And suddenly, on the other side of the bar, their demeanor changed—for the worse. I genuinely enjoy interacting with people, but not when I'm treated like a servant. I’m a human being.

These days, there’s less of that “the customer is always right” mantra. It's more about a mutual exchange. From my perspective and conversations with others in the industry, it's like, “You’re coming into my space. If you were at my house, you wouldn’t act inappropriately, would you? We don’t want you here if you don’t respect us.” There’s no desperate need for affirmation or even their money because it’s just not worth it.

Building this place was a massive undertaking. Bootstrapping, pregnant, with another kid on my hip. I didn’t work this hard to be treated that way.

When we launched Troubadour, we got some unexpected reactions from our regulars at the bakery. They were excited about the new place, but taken aback by the prices and the no-substitution policy. They'd ask, “Why does this sandwich cost this much?” or “Why can't I customize it?” I wanted to tell them, “This isn’t Subway.” They saw the sandwich as a DIY thing, not a curated entrée we put together thoughtfully.

So, in response to your question, I really value when our community approaches us with understanding. I wish they'd realize we're always doing our best, with their interests at heart but without compromising our vision or operation. When they ask, “Can you just make more of this?” I think, “Well, sure, but it'll take four hours.” It's not instantaneous. Offering classes was a game-changer. That's when many truly understood the effort and time involved.

Everything we do—from the timeline, ordering, and sourcing to the cooling process – is carefully considered to produce the best possible product. It's not just about the time it takes, but also the experience and expertise behind each step. There's this story I heard on a podcast about Pablo Picasso. While at a bar, a woman recognized him and handed him a napkin, asking for a quick sketch. In just a few minutes, he handed her something. When she asked about the price, he quoted an amount she found outrageous, given the short time it took him. But Picasso replied, “It's not just 5 minutes; it's 42 years of experience.” That's the essence of our work too.